Beyond the Subsidy Cliff: What the New Obamacare Fight Reveals About the Future of U.S. Health Care

Sarah Johnson

December 9, 2025

Brief

Analysis of the bipartisan push to extend enhanced Obamacare subsidies, the GOP’s HSA-centered alternatives, and what this subsidy cliff reveals about the future structure of U.S. health care.

Obamacare Subsidies Are About to Expire. The Real Fight Is Over What Comes Next.

What looks like a narrow fight over two more years of Affordable Care Act (ACA) premium subsidies is, in reality, a proxy battle over the future architecture of U.S. health care: how much we rely on public subsidies versus tax-favored individual accounts, how much power remains with insurers and intermediaries versus patients, and whether bipartisan dealmaking is still possible in a deeply polarized Congress.

The bipartisan House bill led by Reps. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-Pa.) and Tom Suozzi (D-N.Y.) is not just a stopgap. It’s an attempt to build a bridge between two competing Republican visions (reform Obamacare vs. sidestep it entirely) and a Democratic Party that increasingly sees the ACA as a permanent pillar of the safety net rather than a stepping stone.

Why this matters now

The enhanced ACA subsidies created during the COVID-19 pandemic are set to expire at the end of this year. Without action, roughly 20 million people who rely on ACA marketplaces are poised to see substantial premium hikes, with several million at risk of dropping coverage altogether.

The Biden-era subsidy expansion, initially via the American Rescue Plan (2021) and extended through the Inflation Reduction Act (2022), did three crucial things:

- Increased subsidy amounts for lower-income enrollees.

- Eliminated the old income cliff at 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL), capping marketplace premiums at 8.5% of income even for middle- and upper-middle-income households.

- Helped drive record-low uninsured rates, especially in states that hadn’t expanded Medicaid.

Allowing these subsidies to lapse will not only reverse coverage gains; it will also hand both parties a potent campaign issue in an election cycle where cost-of-living pressures are already central.

The bigger picture: A decade of contested Obamacare

To understand the current standoff, you have to see it as the latest chapter in a decade-long struggle over Obamacare’s legitimacy and permanence.

When the ACA marketplaces launched in 2014, they were shaky. Premium spikes, insurer exits, and narrow networks created a sense that the law might collapse under its own weight. Republicans campaigned on “repeal and replace,” and came within one Senate vote of doing so in 2017.

But since then, three big shifts have occurred:

- Political entrenchment. Like Medicare and Medicaid before it, the ACA has developed powerful constituencies: insurers, hospitals, patients with preexisting conditions, and millions receiving subsidies. Repeal is no longer a serious governing option, even if it remains rhetorical red meat.

- Judicial stabilization. Repeated Supreme Court challenges failed to overturn the law, reducing the sense that the ACA is temporary or legally fragile.

- Pandemic-era normalization of subsidies. The COVID-era enhancements didn’t just patch a crisis; they set new expectations about what “affordable coverage” means, especially for middle-income households.

The current fight centers not on whether the ACA should exist, but on what form federal support for private coverage should take, and what strings (if any) should be attached.

What this really means: Three competing models on the table

Behind the legislative maneuvering are three distinct policy visions.

1. The bipartisan “stabilize and tweak” model

The Fitzpatrick–Suozzi package tries to marry short-term stability with incremental conservative reforms:

- Two-year extension of enhanced subsidies. This blunts the immediate premium spike and gives both parties breathing room beyond the next election cycle.

- Consumer consent and notification requirements. The bill would stop insurers or brokers from changing plans or subsidy allocations without explicit consent and prompt notice—an answer to mounting complaints about “auto-switching” and surprise plan changes in ACA marketplaces.

- Reining in Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). PBMs, which negotiate drug prices and control formularies, have been widely criticized for opaque practices and high spreads. Targeting PBM profits is one of the few truly bipartisan health cost reforms.

- Expansion of Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). HSAs are favored by conservatives because they shift more decision-making (and risk) to individuals. Embedding HSA expansion in a subsidy-extension bill is an attempt to give Republicans a policy win in exchange for accepting the ACA’s architecture for a bit longer.

This model reflects an implicit acceptance that the ACA marketplaces are now a permanent part of the system, but tries to make them more “market-friendly” at the margins.

2. The conservative “HSA-centered” replacement model

Legislation like the Republican Study Committee’s plan to allow states to opt out of Obamacare while massively expanding HSAs represents a deeper ideological challenge: move away from income-based subsidies toward tax-favored individual accounts and state-level experimentation.

In practice, this would likely mean:

- Less predictable coverage for low- and moderate-income people.

- More variation across states in benefit design and consumer protections.

- Shifting more financial risk to individuals, especially those with chronic conditions.

For conservatives, this is about redesigning incentives and curbing federal spending. For Democrats, it reads as a partial rollback of the ACA’s core promise of guaranteed, regulated coverage.

3. The Democratic “lock in and build out” model

Senate Democrats are moving their own bill to extend enhanced subsidies, likely with fewer concessions to Republicans. Their longer-term vision is to make the subsidy expansion permanent, close remaining coverage gaps (particularly in non-expansion states), and potentially move toward more robust public options.

In this model, ACA subsidies are treated as a foundational entitlement, akin to Social Security and Medicare, not as a temporary pandemic-era patch.

What’s being overlooked: The quiet subsidy cliff for the middle class

Most public debate focuses on low-income enrollees, but the enhanced subsidies have been particularly important for households just above the old 400% FPL cutoff—roughly $58,000 for an individual or $120,000 for a family of four.

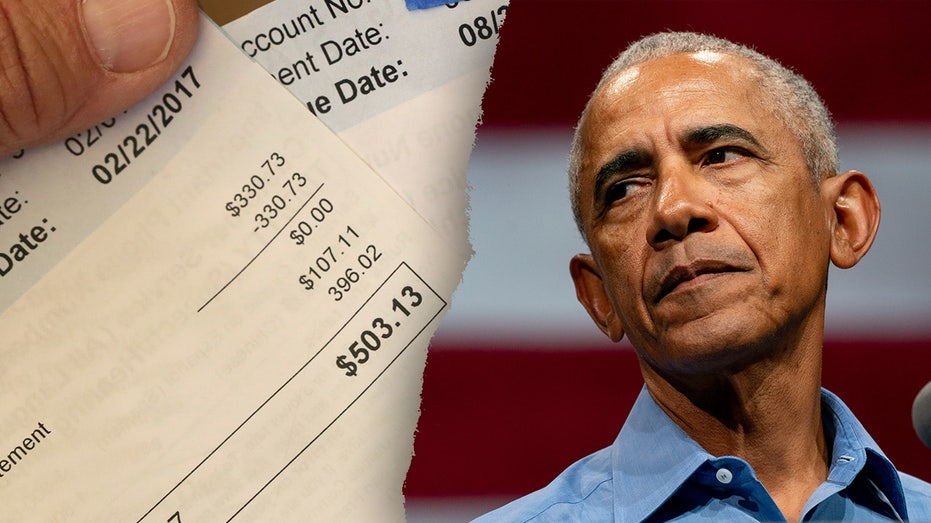

Before the COVID-era changes, a middle-aged family in a high-premium state could easily face $15,000–$20,000 annual premiums with no subsidy. The expanded credits capped their premium at 8.5% of income. When those caps vanish, many of these families will be hit with what is effectively a hidden tax increase.

This is politically sensitive for both parties: these are swing voters in suburban districts that will decide control of the House and Senate. In many ways, the bipartisan bill is less about the poorest Americans—who are more likely to be in Medicaid—and more about shoring up the middle-class voters who have quietly become ACA beneficiaries.

Pressure on Speaker Johnson: Governance vs. purity

House Speaker Mike Johnson faces a familiar but increasingly acute Republican dilemma: does he allow a bipartisan coalition to pass a “patch” that many in his conference dislike, or does he hold out for a more ideologically pure package that almost certainly cannot clear the Senate?

His stated position—that Obamacare is “long-broken” and needs significant reform—echoes the party’s base. But the governing reality is that premium spikes will land squarely on his own constituents, including older and rural voters who disproportionately rely on subsidized individual-market coverage.

Allowing the bipartisan bill to come to the floor—whether directly or via a discharge petition—would risk a revolt among conservatives who see any extension of ACA subsidies as entrenchment. Blocking it risks headlines about families losing coverage or facing four-digit monthly premiums. This is the same political trap that helped sink repeal efforts in 2017; only now, the ACA is even more embedded.

Expert perspectives

Health policy scholars and industry experts see this fight as less about the short-term subsidy window and more about the long-term shape of the market.

Many point to evidence from the last few years. According to federal data, the pandemic-era subsidy expansions helped push U.S. uninsured rates to near-record lows, with marketplace enrollment exceeding 21 million in 2024. Several analyses suggest that ending the enhanced subsidies could cause millions to drop coverage or become underinsured.

At the same time, economists warn that repeatedly extending temporary subsidies without structural reforms may further entrench a high-cost status quo. If insurers and providers expect the federal government to continually backstop premiums, the incentive to control underlying costs weakens.

Data and evidence: What happens if subsidies lapse?

While exact numbers will depend on premiums and incomes in each state, prior projections from the Congressional Budget Office and independent think tanks provide a strong directional picture:

- Premium spikes. Millions of marketplace enrollees would see steep increases in their monthly bills—often several hundred dollars per month for older enrollees in high-cost regions.

- Coverage losses. Estimates have previously suggested that several million people could lose coverage if the enhanced subsidies expire, particularly among those just above Medicaid eligibility but below comfortable middle-class incomes.

- Budget trade-offs. Extending enhanced subsidies for two years is likely to cost tens of billions of dollars. Republicans will push to offset that cost with other cuts or structural reforms; Democrats may argue that the cost is modest relative to the benefits of reduced uncompensated care and better health outcomes.

The inclusion of PBM reforms and HSA expansion is not just window dressing; it’s a recognition that voters care about drug prices and out-of-pocket costs as much as headline premiums. But these reforms operate on different timelines: PBM changes might take years to affect pricing dynamics, while the subsidy cliff hits on January 1.

Looking ahead: A test of whether Congress can still do “must-pass” health policy

Several scenarios are plausible:

- Scenario 1: A narrow, bipartisan two-year deal passes. This would likely involve the House bipartisan bill (or something like it) being tweaked to win 60 votes in the Senate, with both parties claiming partial victory. It would push the fight past the next election and implicitly acknowledge the ACA’s permanence.

- Scenario 2: Temporary failure, last-minute rescue. Leadership in both chambers could initially block a deal, only to scramble in a lame-duck session after premiums spike and political backlash builds. This would mirror earlier brinkmanship over Medicare physician payment cuts and other health cliffs.

- Scenario 3: No extension. If conservatives hold firm and Democrats refuse to swallow HSA-heavy counterproposals, the subsidies could expire. Politically, this would hand Democrats a powerful narrative about Republicans raising health costs, but it would also force Democrats to confront the limits of a subsidy-heavy strategy in a structurally expensive system.

Another wild card is the discharge petition option. If moderate Republicans in swing districts feel sufficiently threatened by premium hikes, they could join Democrats to force a vote over leadership’s objections. That would be an extraordinary rebuke to Johnson and a signal that health care pocketbook issues can still override party discipline.

The bottom line

This is not just a technical fix to “keep Obamacare subsidies alive.” It is a test of whether the U.S. will double down on income-based subsidies as the primary tool for making private insurance affordable, pivot toward individual account-based models favored by conservatives, or stumble into a hybrid by default.

The decision Congress makes—or fails to make—over the next few months will shape not only premiums in January, but the broader trajectory of health reform for the next decade. As with earlier battles over Social Security and Medicare, once a benefit is extended multiple times, it becomes increasingly difficult to roll back. The bipartisan bill is an attempt to harness that political reality without abandoning conservative reform ambitions entirely. Whether Speaker Johnson lets that compromise come to a vote will reveal a lot about which instinct dominates today’s Republican Party: ideological purity or coalition governance.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One underappreciated angle in this fight is the quiet redistribution the enhanced subsidies have already undertaken. Early ACA battles were framed as a transfer from the healthy to the sick and from higher-income taxpayers to lower-income enrollees. But the pandemic-era expansions increasingly redistributed within the middle class, especially from younger, higher-income professionals to older, middle-income households in high-cost regions. That helps explain the political stickiness: these are voters who are not traditionally seen as beneficiaries of ‘welfare’ programs, yet are now structurally reliant on federal subsidies. If Congress extends the subsidies again, it effectively normalizes this intra-middle-class transfer and blurs old lines between safety net programs and broad-based middle-class entitlements. If it doesn’t, the shock will expose just how dependent ostensibly self-sufficient households have become on federal support to navigate a private market that remains stubbornly unaffordable. Either path raises uncomfortable questions for both parties about the kind of health system—and social contract—they are willing to own.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.