Clear as Mud: How the Ravens’ Overturned Touchdown Exposes a Deep Flaw in the NFL’s Catch Rule

Sarah Johnson

December 9, 2025

Brief

The Ravens’ overturned TD vs. the Steelers isn’t just a bad break. It exposes deep flaws in the NFL’s catch rule, replay philosophy, and competitive integrity at the heart of the modern game.

Why the Ravens’ Overturned Touchdown Exposes a Deep Problem With the NFL’s Catch Rule

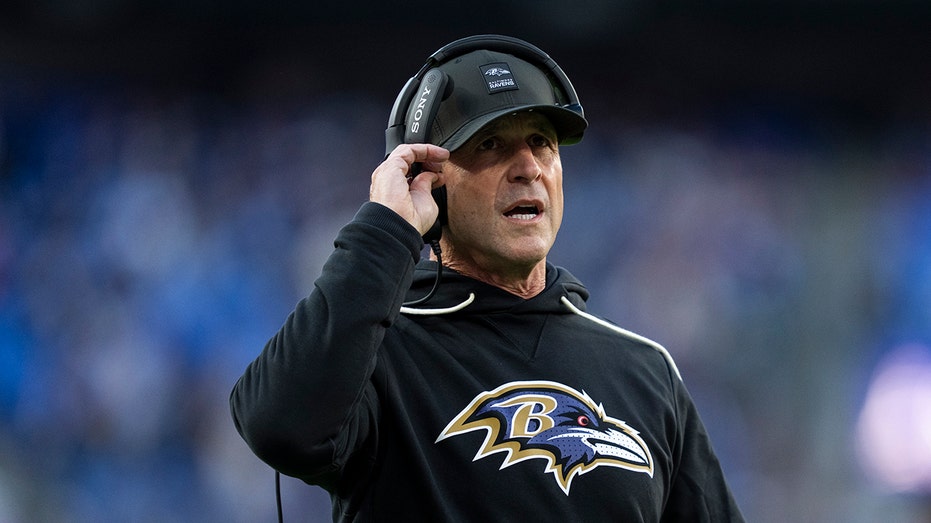

John Harbaugh’s “clear as mud” remark after the Baltimore Ravens’ overturned touchdown against the Pittsburgh Steelers isn’t just a frustrated coach venting after a loss. It’s the latest flare in a long-running crisis of trust between the NFL, its rules, and the people who play, coach, and watch the game. The call on Isaiah Likely’s would-be go-ahead score didn’t just swing a critical AFC North game; it highlighted how the league’s attempt to engineer precision has produced something far more damaging: systemic uncertainty at the core of what football is—the catch.

The league’s explanation, as relayed by VP of Instant Replay Mark Butterworth—control, two feet, then an “act common to the game” that never materialized—perfectly captures the problem. This isn’t language designed for players, coaches, or fans. It’s language for lawyers. And when the judgment of a game-defining play becomes a three-part legal exam, the NFL drifts further away from the intuitive simplicity that made it a mass sport in the first place.

The bigger picture: how we got to this murky catch rule

The NFL’s catch rule has been controversial for more than a decade, and each “fix” has layered new complexity on top of old confusion:

- 2010 – Calvin Johnson play (“The Process”): Johnson appeared to catch a game-winning touchdown for the Lions, controlled the ball, got both feet down, went to the ground, and lost the ball as he stood to celebrate. Officials ruled it incomplete, redefining the public’s understanding of “finishing the process of the catch.” It became the original modern flashpoint.

- 2014–2015 – Dez Bryant in Green Bay: In the Divisional Round, Bryant’s spectacular fourth-down catch was overturned because he was deemed not to have completed the process of the catch as he hit the ground. Dallas fans and neutral observers largely saw a football play; the rulebook saw a technical failure.

- 2017–2018 – Rule overhaul: After years of outcry, the NFL Competition Committee tried to simplify things. The league removed the “going to the ground” requirement and emphasized three pillars: control, two feet (or a body part) in bounds, and an additional act (a third step, reaching, or a move common to the game).

- 2018–present – “Football move” era: The intent was to make controversial calls simpler and more fan-friendly. Instead, judgment shifted to whether a receiver had done enough to constitute a football move, introducing a new gray area instead of resolving the old one.

The Likely play is a classic product of this evolution. According to Butterworth, Likely had control and two feet, but before he could take a third step or make a football move, Joey Porter Jr. ripped the ball out. By the letter of the rule, that’s incomplete. By the spirit of the game—and the instincts of many viewers—it looked like a touchdown broken up by a late defensive play. That disconnect between “what feels like football” and what the rulebook says is the heart of the issue.

What this really means: football’s core act is now a branding risk

At face value, this was one play in one game. But zoom out, and it points to three larger problems for the NFL:

- Competitive integrity under strain: In a five-point divisional game, an overturned touchdown with under three minutes left is not just a bad break; it’s potentially the difference between winning the AFC North and scrambling for a wild card. When multiple high-leverage calls are later admitted to be wrong or hotly disputed, the legitimacy of outcomes comes into question, especially when playoff seeding and careers hang in the balance.

- Fan confidence and emotional investment: Fans will tolerate human error; they’ll tolerate bad calls. What they don’t tolerate well is systemic, rule-driven confusion. If people watching at home—and even former quarterbacks like Tony Romo—can’t consistently predict what’s a catch, the shared language of the sport breaks down. The more fans feel the game is decided by arcane interpretations rather than performance, the more fragile their trust becomes.

- Replay technology vs. the soul of the game: Instead of clarifying football, slow-motion replay often weaponizes ambiguity. The camera zooms in, time slows, and microscopic bobbles or timing differences—imperceptible at full speed—become decisive. The Ravens-Steelers game shows how replay can replace “did he make a football play?” with “can we find a frame that supports an overturn?”

Harbaugh’s comment—“clear as mud”—resonates because it captures what coaches across the league privately admit: they no longer know, with confidence, how key plays will be ruled in real time. That uncertainty complicates play design, challenges, clock management, and risk calculation.

The overlooked layer: mental calculus on the field

What rarely gets discussed is how this rule affects player behavior. Receivers are now coached not just to secure the ball, but to “sell” a catch to the replay booth—tuck it immediately, take extra steps, exaggerate the football move. Defenders are trained to rip the ball late, knowing that if they disrupt the sequence before the rulebook’s checklist is complete, they can turn what looks like a catch into an incompletion.

In the Likely play, Porter Jr. executed that defensive philosophy perfectly. From a defensive coaching perspective, this is the modern technique: never concede the play as dead until the receiver has clearly survived the rulebook. But when defenders are playing to the language of the rule instead of the whistle, the game’s organic flow is replaced by a kind of legal choreography.

Expert perspectives: why the rule keeps failing under pressure

What makes this episode especially telling is the split in real time: Romo saw a touchdown, Gene Steratore (a former official) agreed with the overturn. That divide mirrors a larger pattern—players and analysts see football; rules technicians see legal compliance.

Sports law scholar Prof. Michael McCann has often noted that the NFL’s rulebook is "less a manual of sport than a liability document." The catch rule reflects that philosophy. It’s constantly refined in response to controversy, legal risk, and competitive equity concerns, but it’s rarely evaluated for emotional clarity and coherence to the layperson’s sense of fairness.

Former NFL VP of Officiating Dean Blandino has long argued that replay should defer to the call on the field unless there is "clear and obvious" evidence to overturn. The Likely call tests that standard: when experienced analysts are split, was the evidence truly clear and obvious? Or has the standard drifted toward “if we can technically justify an overturn, we will”?

Former Ravens receiver Torry Holt has previously highlighted a related issue: “Receivers don’t know if it’s enough to catch it and get down. They’re thinking, ‘Do I need one more step? Two? Do I need to reach?’ That hesitation changes how you play.” Plays like Likely’s show how rule-driven second-guessing isn’t just post-game commentary—it’s baked into live decision-making.

Data & evidence: this isn’t an isolated perception problem

The NFL doesn’t publish granular public stats on “controversial” calls, but independent tracking gives some clues:

- In recent seasons, between 40–55% of coach’s challenges on catches have been reversed, indicating how often the on-field judgment differs from the slow-motion interpretation.

- In fan surveys conducted by outlets like the NFLPA and independent sports analytics firms, the catch rule consistently ranks among the top two most confusing rules, alongside roughing-the-passer.

- Broadcast data suggests that games with high-profile overturned catches generate significantly higher post-game complaint volume on social media and talk shows, especially when they swing late-game win probabilities.

Add to this game the other officiating issues: an admitted erroneous unsportsmanlike conduct penalty that gave Pittsburgh four extra points, and a reversed interception that would have given Baltimore prime field position. The cumulative effect isn’t just frustration; it’s a statistical distortion that could decide playoff paths in a tight division race.

Division stakes: why this matters far beyond Week 13

This wasn’t some midseason game between teams drifting out of contention. It was a swing contest in arguably the NFL’s most physical, emotionally charged division. The Steelers moved to 7–5 and into sole possession of the AFC North lead; the Ravens fell to 6–7. In a conference where wild-card spots are often decided by tiebreakers and head-to-head records, this single overturned catch could be the difference between:

- Hosting a playoff game vs. traveling as a wild card

- Needing to win in Week 18 at Acrisure Stadium vs. having margin for error

- Ownership viewing a season as a success vs. a disappointment—decisions that affect coaching staff, roster turnover, and long-term strategy

From a coach’s perspective, the brutal reality is this: you can spend a week building a game plan, your players can execute under pressure, and still find your fate decided by how a rule interpreter understands “act common to the game” at 240 frames per second.

Looking ahead: what needs to change

The NFL has three realistic paths forward on the catch rule, and the Likely play underscores the urgency of choosing one.

- Re-center the rule on intuitive football: The league could simplify to a standard closer to, “If a player secures the ball, gets two feet down, and is then contacted, it’s a catch unless the ball clearly never came under control.” That would mean more fumbles and fewer incomplete passes in borderline cases, but it would align better with how players and fans understand football in real time.

- Narrow replay’s scope on catches: Limit replay review on catches to objective elements—feet in bounds and obvious bobbles. “Act common to the game” could be left as an on-field judgment, reversible only in extreme cases. That restores some authority to officials and reduces the slow-motion reinterpretation phenomenon.

- Clarify and codify “football move” with real transparency: If the league insists on keeping the current structure, it needs to publish standardized, video-backed examples and decision trees: what counts as a third step, what counts as a reach, and how much time is required. That won’t solve every edge case, but it would at least move from abstract legal phrases to concrete, teachable standards.

Regardless of which path it chooses, the NFL cannot dismiss Harbaugh’s criticism as simple sour grapes. When coaches across the league echo the same complaint—that they can’t explain the rule to their own locker rooms—that’s not a PR problem; it’s a governance problem.

The bottom line

The Isaiah Likely non-touchdown against the Steelers will be remembered in Baltimore as a painful turning point in a crucial divisional game. But its real significance lies in what it reveals: a sport whose most basic act has become a moving target.

The NFL has built an empire on shared understanding—fans, players, coaches, and officials all recognizing, at a glance, what just happened. The more that understanding is replaced by legal parsing of “control, two feet, and an act common to the game,” the more the league risks undermining both its credibility and its emotional power.

Harbaugh’s “clear as mud” line isn’t just a jab at a rule he doesn’t like. It’s a warning that the league’s quest for technical perfection may be eroding the intuitive clarity that made football the dominant sport it is. Until that’s addressed, no amount of slow-motion replay or postgame pool reports will fix the feeling that, in too many games, the rules—not the players—are deciding the outcome.

Topics

Editor's Comments

What’s most striking about this episode is that everyone is technically right—and that’s precisely the problem. By the current rule, the replay center can justify calling Likely’s play incomplete. Harbaugh, Romo, and a huge share of fans are also justified in feeling they just watched a touchdown taken off the board. That gap between technical correctness and perceived fairness is where the NFL is playing a dangerous game. When the league talks about “clarifying” the catch rule, it often means adding more words and sub-conditions. But the sport’s legitimacy depends on the opposite direction: fewer words, more shared intuition. There’s also an underexplored power dynamic here. Centralized replay control shifts decisive authority away from the stadium and from officials who are accountable in real time to a remote hub insulated from the emotional stakes of the moment. If the league doesn’t recalibrate toward simpler, more intuitive standards, we’re likely to see more games—and possibly postseason runs—defined less by athletic performance and more by how a small group of technicians read a dense rulebook in slow motion.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.