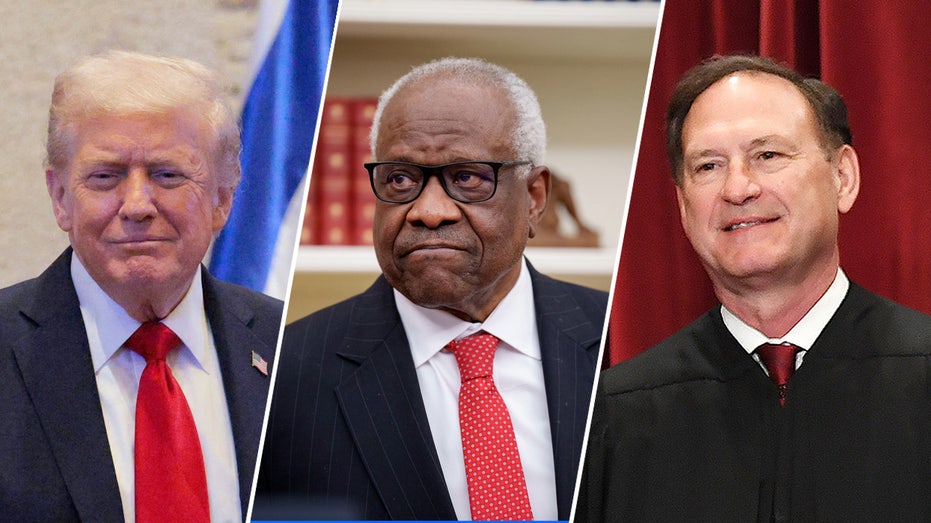

Trump, Alito, and Thomas: How Quiet Retirement Pressure Exposes a Supreme Court Power Struggle

Sarah Johnson

December 9, 2025

Brief

Trump’s defense of Justices Alito and Thomas reveals how age, partisan timing, and legitimacy battles are reshaping Supreme Court politics and fueling a decades-long struggle to lock in ideological control.

Why Pressure on Alito and Thomas Matters Far Beyond Two Seats on the Court

Donald Trump’s public defense of Supreme Court Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas — dismissing GOP chatter about encouraging them to retire as they age into their mid‑70s — looks, on the surface, like routine praise of ideological allies. In reality, it exposes a deep shift in how both parties now view the Supreme Court: not as a fixed constitutional institution, but as a battlefield where timing, health, and partisan control of the Senate are strategic weapons.

What’s really at stake isn’t just whether two justices retire. It’s the emerging norm that Supreme Court seats are to be optimized for partisan advantage, the intensifying legitimacy crisis facing the Court, and the implications of potentially locking in a hard-right majority for another generation.

The bigger picture: A decades-long partisan arms race over the Court

The quiet pressure some Republicans are reportedly applying to Alito (75) and Thomas (77) fits into a well-established pattern: both parties now treat Supreme Court exits as political events that must be managed, not simply as personal decisions.

Three historical milestones frame this moment:

- Thurgood Marshall and the risk of late retirement (1991): The liberal civil-rights icon stayed on the Court into his 80s, resigning under a Republican president, George H.W. Bush. His replacement: Clarence Thomas, one of the Court’s most conservative justices — and now at the center of the current controversy. For progressives, Marshall’s timing became a cautionary tale.

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s decision to stay (2013–2020): Many Democrats urged Ginsburg to retire during President Obama’s second term. She declined. When she died in 2020, Republicans rushed to confirm Amy Coney Barrett weeks before the election, giving conservatives a 6–3 supermajority. That episode made “strategic retirement” a central obsession of judicial politics.

- The McConnell doctrine (2016 & 2020): Senate Republicans blocked Obama’s 2016 nominee, Merrick Garland, on the grounds that it was an election year, then reversed course in 2020 to confirm Barrett days before the election. The Court became a blunt instrument of raw power politics, and the old norms of deference and timing evaporated.

Against that backdrop, some Republicans now see Alito and Thomas as high-value assets whose continued presence — or carefully timed retirement under a Republican president and Senate — could determine the ideological tilt of the Court until the 2050s. Trump’s public line — “I hope they stay… I think they’re fantastic” — sits uncomfortably next to that strategic calculus.

What this really means: Age, health, and the new politics of judicial longevity

The underlying anxiety driving the reported GOP pressure is demographic and brutally practical: time. The Court’s older justices — Alito (75), Thomas (77), and liberal Sonia Sotomayor (71) — are on the front lines of a generational transition whose outcome will likely define constitutional law for decades.

Republicans are calculating from a painful lesson Democrats learned with Ginsburg: if an aging justice dies or becomes incapacitated under a president of the opposite party, the ideological balance can swing dramatically. That fear — not abstract theory about judicial independence — is what animates discussions about retirement timing.

What’s different today is how openly this is discussed within political circles. Instead of pretending that justices occupy some apolitical Olympus, party strategists treat them as long-term investments whose “yield” can be maximized by aligning retirement with unified party control of the White House and Senate.

Trump’s public defense of Alito and Thomas serves several simultaneous purposes:

- Signaling loyalty to the conservative base: Alito and Thomas are heroes to movement conservatives for their role in dismantling abortion rights, curbing administrative power, and expanding gun rights. Trump praising them as “fantastic” reassures a skeptical legal establishment that he’ll protect their champions.

- Deflecting intra-party awkwardness: Openly pushing two sitting justices to retire to help Trump stack the Court further could look crass and power-hungry. By saying he wants them to stay, Trump distances himself from that pressure while still benefitting if they ultimately retire on “their own terms.”

- Reframing the legitimacy debate: Alito and Thomas are lightning rods for critics who say the Court is overly politicized — particularly after the Ginni Thomas Jan. 6 texts and Alito’s role in Dobbs. Trump’s praise tacitly rejects those concerns and casts them as purely partisan attacks.

Why Alito and Thomas are uniquely contentious

Alito and Thomas aren’t just any conservative justices. They anchor the Court’s right flank with a jurisprudential approach that is both deeply transformative and deeply polarizing.

Clarence Thomas:

- Has advocated for revisiting or overturning long-standing precedents on issues ranging from same-sex marriage to contraception access.

- Is at the center of ethics controversies, including undisclosed luxury travel and gifts, and his wife Ginni Thomas’s involvement in efforts to overturn the 2020 election, including texts to Mark Meadows urging the White House to challenge Trump’s loss.

- Has repeatedly declined to recuse from cases touching Jan. 6 and election issues, despite his wife’s activism, triggering calls from some House Democrats in 2022 for his impeachment or resignation.

Samuel Alito:

- Authored the majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade and ended federal constitutional protection for abortion rights.

- Is widely viewed by conservatives as the intellectual architect of the Court’s new direction on religion, abortion, and regulatory power.

- Is portrayed by allies as indifferent to political or partisan pressures; a source close to Alito told reporters he has “never thought about this job from a political perspective” and would not retire for political reasons.

Because both justices are so central to the Court’s rightward trajectory, their potential departure isn’t merely about filling two seats — it’s about whether the conservative revolution in constitutional law stays locked in or faces a potential rollback over time.

Expert perspectives: Legitimacy, ethics, and the strategic-retirement dilemma

Legal scholars are divided, not so much on whether politics drives retirement decisions — most privately concede it does — but on what that means for the Court’s legitimacy.

Harvard Law Professor Richard Fallon has long warned that “when the public comes to see justices as partisan actors in robes, the Court’s authority depends less on law and more on raw political power.” In that context, both the quiet pressure to nudge justices off the Court and the visible ethics controversies around Thomas and Alito become mutually reinforcing: they feed a narrative that the Court is just another political branch.

On the other side, conservative scholars argue that open recognition of ideological stakes is more honest than clinging to the fiction that justices are neutral umpires. George Mason University’s Ilya Somin has noted that “nomination and confirmation have always been political; pretending otherwise doesn’t make the process any less partisan.” From this perspective, strategic retirement is simply rational behavior in a polarized era.

What’s often missing from mainstream coverage is how the Thomas and Alito debates intersect with a broader, structural problem: the absence of term limits.

Federal judges enjoy life tenure under the Constitution, but many constitutional scholars have proposed 18-year staggered terms for Supreme Court justices. This would regularize appointments (one every two years), reduce the incentive for justices to time their departures, and lower the stakes of any single vacancy. Yet both parties, for now, benefit from the existing system — at least when they’re in power.

Data & evidence: How unusual is this level of ideological entrenchment?

A few data points help frame what’s at stake:

- Tenure length: In the 19th century, Supreme Court justices served an average of about 15 years. Today, the average tenure is closer to 26–29 years. If a 50-year-old justice is appointed today, they could easily shape law into the 2050s or 2060s.

- Age at retirement: Since 1970, the average age of retirement or death for justices has hovered in the mid‑70s to early‑80s. Alito (75) and Thomas (77) are at the point where health becomes a serious actuarial concern for party strategists.

- Public confidence: Recent polling has shown trust in the Supreme Court near historic lows, with some national surveys placing confidence in the institution in the 35–40% range — sharply down from historic norms above 60%.

- Partisan alignment: For the first time in modern history, the Court has a sustained 6–3 conservative majority aligned with one party’s policy agenda across abortion, guns, religion, and regulation.

Those numbers underline why even the possibility of replacing Alito or Thomas under a different partisan configuration is so consequential.

Looking ahead: What to watch, and what’s being overlooked

There are several key dynamics to watch in the coming years that will reveal how this tension plays out.

- Whether quiet pressure becomes public pressure: As election cycles approach, will Republican senators or conservative activists openly argue that Alito and Thomas should step aside to “secure the Court”? If that happens, it could backfire by making any retirement look blatantly partisan.

- Democratic mirror-image calculations: While Republicans fret over Thomas and Alito, Democrats are equally anxious about Justice Sonia Sotomayor, 71, with past health concerns and a liberal voting record. Progressive voices increasingly warn that if Democrats regain unified control, they must encourage strategic retirement on their side as well — even as they criticize the practice when Republicans do it.

- Ethics reform and recusal standards: Thomas’s refusal to recuse from Jan. 6–related cases, despite his wife’s activism, will remain a flashpoint. If more disclosures emerge about outside influence or undisclosed gifts, bipartisan support for binding ethics rules could grow — especially if the Court rules on cases involving Trump, the administrative state, or election law.

- Structural reform debates: If the Court continues to hand down sweeping, unpopular decisions in areas like abortion, voting rights, or presidential power, expect renewed debate about term limits, court expansion, or stripping the Court of jurisdiction in certain areas. Even if these reforms don’t pass, the debate itself further politicizes the Court.

- Trump’s own legal stakes: The article notes that the Court is poised to rule on a case involving Trump’s bid to fire an FTC commissioner, potentially overturning a 90‑year-old precedent on independent agencies. As Trump’s legal interests intersect with the Court’s docket, scrutiny of the relationship between a former president and justices he praises — and in some cases appointed — will intensify.

An overlooked dimension is how these dynamics affect lower courts. If justices increasingly act as long-term partisan actors, presidents and senators will double down on appointing younger, more ideologically reliable judges to the appellate courts as a pipeline. That risks entrenching polarization throughout the judiciary, not just at the top.

The bottom line

Trump’s praise of Alito and Thomas is not just a simple gesture of support. It is a window into a judiciary that has become central to partisan strategy, where age and health are treated like political commodities and where the line between impartial justice and ideological project grows thinner each term.

Whether Alito and Thomas stay or go, the fight over their seats underscores a larger reality: until the structure of Supreme Court tenure changes, every vacancy — and every birthday of an aging justice — will be treated as a high-stakes moment in America’s constitutional power struggle.

Topics

Editor's Comments

What gets less attention in today’s debate over Alito and Thomas is how both parties are quietly converging on the same playbook while publicly condemning each other for using it. Republicans are worried about losing aging conservative justices; Democrats are worried about losing aging liberals like Sonia Sotomayor. Each side invokes high-minded principles—judicial independence, ethics, constitutional duty—when criticizing the other, then reverts to hard-nosed strategic logic when talking about their own nominees. That symmetry matters because it suggests the problem is structural rather than purely partisan: life tenure in a hyper-polarized democracy invites exactly this kind of brinkmanship. Until there is serious movement on term limits or regularized appointments, we should expect every Supreme Court vacancy—or even the possibility of a vacancy—to be treated as a constitutional crisis in miniature. The Alito-Thomas story is not an aberration; it may be the new normal.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.