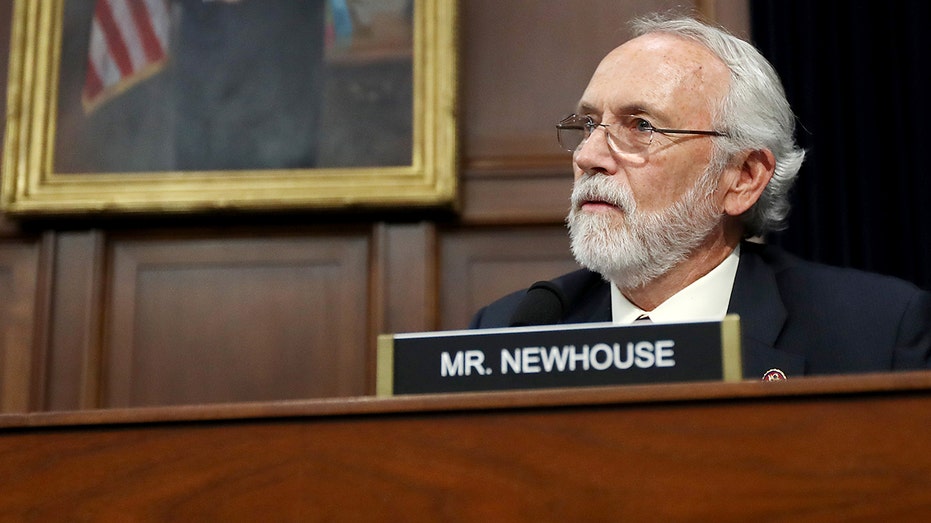

Dan Newhouse’s Exit and the Near-Extinction of Anti‑Trump Republicans in the House

Sarah Johnson

December 17, 2025

Brief

Dan Newhouse’s retirement marks the near-extinction of House Republicans who backed Trump’s second impeachment, highlighting how Trumpism has reshaped GOP incentives, primaries, and the party’s capacity to govern.

Dan Newhouse’s Exit Isn’t Just a Retirement. It’s the End of an Era for Anti‑Trump Republicans.

Rep. Dan Newhouse’s decision not to seek re-election isn’t simply another retirement announcement. It marks the near-extinction of a specific Republican species: lawmakers willing to formally break with Donald Trump at the peak of his power and accept the consequences.

With Newhouse gone, Rep. David Valadao of California could soon stand as the lone remaining House Republican who voted to impeach Trump after January 6 and survived at least one subsequent election. That’s a symbolic milestone, but it’s more than symbolism — it shows how thoroughly Trump and Trumpism have reshaped the party’s internal incentives, candidate pipeline, and willingness to tolerate dissent.

The slow purge of the impeachment Republicans

In January 2021, ten House Republicans joined Democrats in voting to impeach Trump for “incitement of insurrection” after the Capitol attack. At the time, many analysts saw the vote as a test of whether the GOP would begin distancing itself from Trump or double down. We now know which path won.

Of those ten, eight are already gone from Congress: Liz Cheney, Anthony Gonzalez, Jaime Herrera Beutler, John Katko, Adam Kinzinger, Peter Meijer, Tom Rice, and Fred Upton. Most either retired or were defeated in primaries after facing intense backlash and Trump-backed challengers. That left three survivors: Newhouse, Valadao, and for a time, Rice before he lost his subsequent primary.

Newhouse’s departure continues a pattern that stretches beyond Trump: moderate or institutionalist Republicans, especially those in swing or light-red districts, are exiting at higher rates than their Trump-aligned colleagues. What makes Newhouse different is that he is not being directly forced out by voters — he just won re-election in 2024 despite a full-throated Trump challenge. He is choosing to leave, and that choice says something about how governable the conference has become for lawmakers like him.

A historical echo: from Rockefeller Republicans to MAGA dominance

This moment parallels earlier ideological realignments in both parties. In the 1960s and 1970s, so-called Rockefeller Republicans — more moderate, business-oriented, and often socially liberal — were gradually displaced by Goldwater and then Reagan conservatives. Many stayed in the party but lost primaries or became increasingly marginalized. Over time, the party’s center of gravity shifted so dramatically that the old wing became almost unrecognizable.

Today’s transformation is similar in structure but different in kind. The MAGA realignment is less about traditional conservative policy and more about:

- Personal loyalty to Trump as a defining axis of intra-party legitimacy.

- Populist grievance politics focused on cultural identity, immigration, and perceived elite betrayal.

- Procedural hardball, including willingness to challenge election outcomes and disrupt institutional norms.

Newhouse, a conventional conservative who worked “very closely and successfully with President Trump” on policy but broke with him over January 6, represents the older model of GOP legislator: farm-district oriented, focused on agriculture and local economic issues, and operating within traditional institutional lines. His impeachment vote was not the act of a NeverTrump ideologue; it was a line-drawing moment where institutional loyalty — to Congress and the Constitution — briefly outweighed party loyalty.

The fact that there is now almost no space left for that profile at the federal level is the real story.

What Newhouse’s exit really signals inside the GOP

Three dynamics stand out.

1. The completion of Trump’s “deterrence campaign”

Trump’s well-documented efforts to oust impeachment supporters — backing challengers, blasting them publicly as “RINOs,” and celebrating their defeats — were never just about revenge. They served a strategic deterrent function: show every other ambitious Republican what happens if you break ranks on Trump personally.

Even though Newhouse survived a Trump-backed primary challenge in 2024, the message to the broader party was clear: crossing Trump guarantees years of harassment, primary challenges, and public attacks. That kind of deterrence doesn’t need to win every battle; it just needs to make dissent look exhausting and ultimately futile.

Newhouse leaving after weathering that storm reinforces the lesson: you might survive, but you will govern in a conference where your brand of independence is rapidly going extinct.

2. The shrinking caucus of institutional conservatives

Newhouse was not a headline-seeking bomb-thrower. His profile fits what political scientists sometimes label “institutional conservatives” — members who prioritize committee work, policy detail, and incremental gains for their districts. These lawmakers often bridge intra-party divides and make coalitions possible.

As figures like Newhouse and Upton leave, they are replaced disproportionately by more confrontational conservatives backed by groups like the House Freedom Caucus. That shifts the internal balance of power in subtle but important ways:

- Negotiations with Democrats or the White House become politically riskier.

- Compromise budgets, immigration deals, or foreign aid packages are harder to move through the House.

- Leadership faces more frequent internal rebellions, as we’ve seen with repeated speaker showdowns and rule votes failing.

Newhouse’s Washington-based district is safely Republican, so his eventual replacement will almost certainly be GOP. The more interesting question is what kind of Republican: one rooted in agricultural policy and incrementalism, or a Freedom Caucus-aligned insurgent focused on national ideological battles. Trump already endorsed an ultra-conservative challenger, Jerrod Sessler, in 2024; that infrastructure will be poised to try again in an open seat race.

3. The fading of January 6 as an internal moral line

In the immediate aftermath of January 6, there was a brief window when some Republicans openly condemned Trump’s role and floated the idea of moving on. That window slammed shut quickly. Today, punishment for those who voted to impeach continues; meanwhile, rejecting the premise that the 2020 election was stolen can be politically perilous in many GOP primaries.

Newhouse’s retirement underscores how short-lived that moment of institutional self-correction was. Four years after the attack, the party is not only unwilling to revisit accountability; it has largely inverted the narrative, casting impeachment supporters as traitors and Trump as a victim.

Why this matters beyond one congressional seat

Newhouse’s exit has implications that extend beyond Washington’s 4th District.

Primary politics will intensify

Open seats are prime targets for ideological factions. In safe Republican districts like Newhouse’s, the real contest is the primary. With Trump-aligned candidates already having tried to unseat him, it is highly likely an open primary will draw multiple MAGA and Freedom Caucus-oriented contenders, some with Trump’s endorsement.

The result tends to be a race to the right, not just on policy but on personal loyalty to Trump and hardline positions on elections, immigration, and cultural issues. That, in turn, shapes the type of Republicans who enter Congress and how they behave once there.

Governing will get harder, not easier

Every time an institutionalist leaves and is replaced by a hardliner, the margin for dealmaking shrinks. We’ve already seen how a small number of hard-right members can paralyze the House — from deposing a sitting Speaker to blocking routine procedural votes.

If Newhouse is replaced by a member more aligned with the Freedom Caucus, the next Speaker (of either party) will face narrower pathways to cobbling together coalitions for must-pass legislation like funding the government, raising the debt ceiling, or approving emergency aid packages.

The cultural signal to future Republicans

Newhouse’s trajectory sends a strong informal message to younger Republicans watching the landscape: even if you survive crossing Trump once, it will define your career, attract relentless pressure, and leave you increasingly isolated as your cohort disappears.

That message shapes the internal culture of the party more powerfully than any formal rule. It helps explain why, despite periodic private grumbling about Trump’s downsides, so few incumbent Republicans publicly break with him, even after criminal indictments and ongoing legal drama.

Expert perspectives on what’s really at stake

Political scientists and party strategists see Newhouse’s retirement as part of a longer-term structural trend.

Partisan polarization and the geographic sorting of voters have produced fewer competitive districts and more ideological homogeneity in primaries. In that environment, the decisive constituency for many Republicans is not the median voter in November, but the most engaged, often most pro-Trump primary voters in June or August.

Scholars like Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky, who study democratic backsliding, emphasize the importance of “gatekeeping” by mainstream parties — the willingness to marginalize authoritarian-leaning actors within their own ranks. The purge or departure of impeachment supporters like Newhouse signals the opposite: the gatekeepers are either losing influence or leaving the building.

At the same time, GOP strategists warn that while such candidates may perform well in deep-red districts, the cumulative effect can be damaging in swing suburbs and statewide races, where Trump’s brand is more polarizing. The party’s internal incentives, however, remain tilted toward satisfying the base, not moderating for general elections.

Data points that reveal the deeper trend

- 10 House Republicans voted to impeach Trump in 2021. After Newhouse’s departure, only Valadao is likely to remain, and even he faces constant political vulnerability.

- 8 of the 10 have already left Congress voluntarily or after losing primaries — an unusually high attrition rate for relatively senior members.

- Recent Congresses have seen elevated retirement rates among moderate and institutionalist members in both parties, but especially among Republicans who clash with Trump.

- Freedom Caucus membership and influence have grown, while the number of self-identified moderates has shrunk — reflected in voting records, caucus affiliations, and leadership contests.

Looking ahead: what to watch in Newhouse’s district and beyond

Several key questions will shape the next chapter:

- Who consolidates the primary field? If multiple MAGA-aligned candidates split the vote, a more traditional conservative could still win. If the movement coalesces around one candidate, the district will almost certainly send a Trump loyalist to Congress.

- Does Trump re-engage? Having already tried to unseat Newhouse once, Trump and his allies are well positioned to make this open seat a showcase for enforcing loyalty.

- Does any Republican run explicitly on independence? The presence — or absence — of candidates who publicly affirm the 2020 results or criticize January 6 will be a telling indicator of how much political space remains for dissent in safe GOP districts.

- How does this affect House dynamics? The cumulative effect of retirements like Newhouse’s will matter when the next Speaker attempts to pass contentious legislation with a narrow majority and a more ideologically rigid conference.

The bottom line

Dan Newhouse’s retirement is not just the story of a veteran lawmaker stepping down after decades of service. It’s the latest chapter in a long-running internal struggle over what the Republican Party stands for — and who it belongs to.

With his departure, the class of Republicans who were willing to impeach Trump after January 6 is effectively disappearing from the House. Their exit doesn’t mean the doubts they voiced have vanished; it means those doubts are increasingly expressed only in private, if at all. The party that emerges on the other side will be more ideologically cohesive, more loyal to Trump personally, and far less tolerant of internal dissent.

For American governance, that likely means more intense partisanship, more fragile congressional leadership, and fewer lawmakers positioned — or incentivized — to broker cross-party deals. Newhouse’s announcement is a reminder that the most important political changes sometimes happen not with a dramatic election night upset, but with a quiet decision not to run again.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One underappreciated aspect of Newhouse’s retirement is how much it illustrates the quiet power of exhaustion in American politics. It’s easy to focus on the operatic moments — Trump’s Truth Social attacks, primary night upsets, dramatic floor fights — but the system often changes because people like Newhouse simply decide the cost of staying outweighs the benefits. The political science literature tends to frame this as an elite-level calculation about ambition, risk, and opportunity, yet there is also a human dimension: governing in a hyper-polarized environment, under constant pressure from your own base, with shrinking room for nuanced positions, is draining. When enough institutionalists either retire or are replaced, the system doesn’t collapse overnight; it gradually loses ballast. The danger isn’t just more noise or partisan theater. It’s that, over time, there are fewer and fewer members with both the inclination and the political capital to say no when their own side edges toward more extreme tactics or narratives. Newhouse’s exit won’t cause that dynamic, but it makes it a little stronger and a little more durable.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.