Jared Isaacman’s NASA: Billionaire Power, SpaceX Influence, and the New Politics of Space

Sarah Johnson

December 18, 2025

Brief

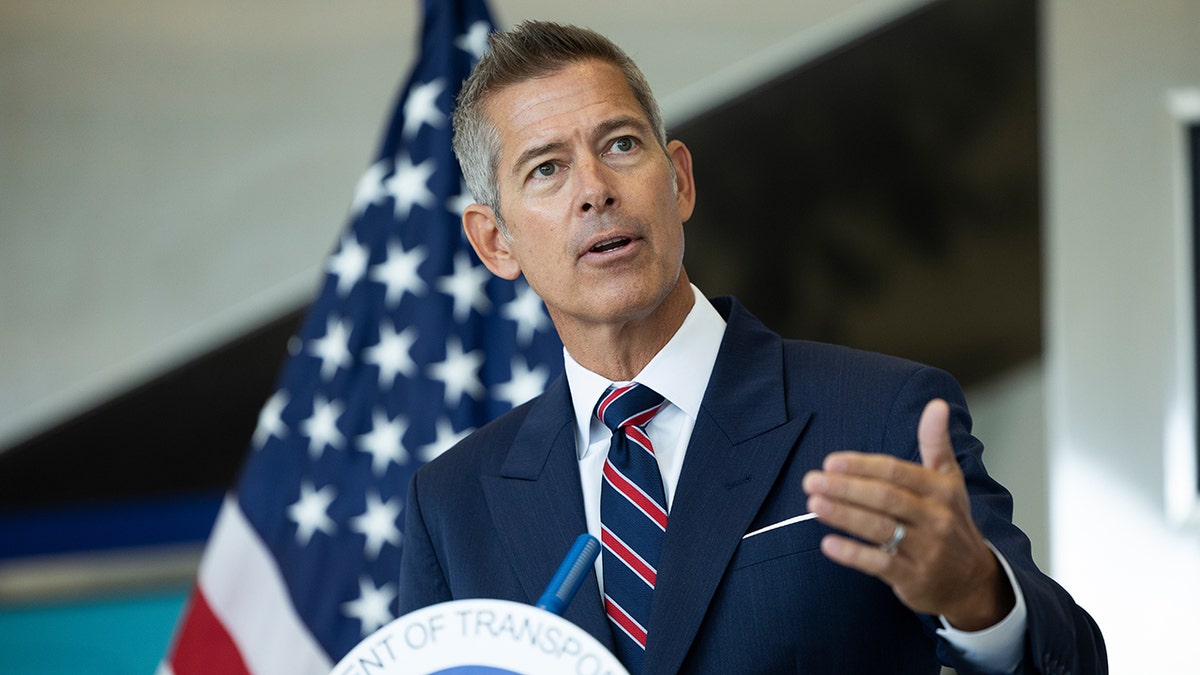

Jared Isaacman’s confirmation as NASA chief marks a turning point in the U.S. space program—entrenching commercial dominance, testing ethics around billionaire influence, and reshaping America’s position in the global space race.

Jared Isaacman Takes Over NASA: How a Billionaire Astronaut Signals a New Era of Politicized, Privatized Space Power

The Senate’s 67–30 confirmation of Jared Isaacman as NASA administrator is more than a personnel move or a feel‑good story about a private astronaut running the agency. It’s a pivot point in three interconnected battles: the struggle over who really controls America’s space future (government or billionaires), the weaponization of space policy inside U.S. politics, and a global race where NASA is no longer the only—or even the central—player.

Seen in isolation, the story is about a billionaire SpaceX investor with a history of private missions who survived a Trump–Musk feud and ultimately prevailed. In context, it marks the clearest institutional endorsement yet of a model where NASA becomes a strategic orchestrator of commercial empires rather than the primary builder of space hardware.

From Apollo to Artemis to Isaacman: How NASA Got Here

To understand the stakes, it helps to remember how different NASA’s role looked even 20 years ago.

- Apollo era (1960s–1970s): NASA led everything—from designing rockets to running missions—anchored in Cold War competition with the Soviet Union. Contractors served the agency; they didn’t define it.

- Shuttle and ISS era (1980s–2000s): NASA still designed and ran core systems (Space Shuttle, International Space Station), but cost overruns and disasters like Challenger (1986) and Columbia (2003) eroded political patience for NASA as a vertically integrated operator.

- Commercial era (2010s–2020s): Under the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) and Commercial Crew programs, NASA shifted to buying services from private firms—most notably SpaceX. This quietly rewired the power balance: the government became the anchor customer, not the prime architect.

By the time the Artemis program to return humans to the Moon ramped up, SpaceX and other private firms were no longer junior partners. They were indispensable. SpaceX now carries NASA astronauts, resupplies the ISS, and holds a contract for a version of Starship to serve as the human landing system for Artemis.

Isaacman’s confirmation codifies this trajectory at the leadership level: the administrator is not just comfortable with commercial dominance—he is personally invested in it, financially and reputationally.

The Politics Behind the Feud: Why Isaacman’s Nomination Became a Proxy Fight

On paper, Isaacman is an easy confirmation: successful entrepreneur, experienced private astronaut, direct mission experience with SpaceX, vocal supporter of U.S. space leadership, and no obvious ethical scandals in public view. The months‑long drama around his nomination was never really about his résumé; it was about power, loyalty, and who gets to shape the frontier economy of the 21st century.

When Trump withdrew Isaacman’s nomination in May, citing a “thorough review of prior associations,” it coincided with a very public rupture between the president and Elon Musk over Trump’s signature “One Big, Beautiful Bill.” Musk called the bill a “disgusting abomination.” Trump called Musk “CRAZY” and said his patience was “wearing thin.”

Isaacman, as a visible Musk ally and SpaceX investor, became collateral damage. As he himself acknowledged, the timing wasn’t a coincidence and he was a “good, visible target.” In Washington, that’s a familiar pattern: when relationships sour with a powerful patron, their associates are often the first to feel it.

What changed was not Isaacman’s qualifications, but Trump and Musk’s political calculus. By fall, signs of détente—handshakes at public events, praise exchanged on X, Musk’s reported financial backing for Republican House and Senate candidates—repositioned Musk from internal critic to strategic ally. Isaacman’s nomination then re‑emerged as a symbol of reconciliation and a way to bind the Musk–Trump orbit more tightly to NASA, and vice versa.

The confirmation vote—67–30—is wide enough to show bipartisan comfort with Isaacman’s technical and managerial credentials, but narrow enough to signal real concern about the precedent: a major federal science agency led by a billionaire intimately tied to one of its dominant vendors.

What Isaacman’s NASA Could Look Like

The most important question isn’t whether Isaacman will be “pro‑commercial space.” That’s already the bipartisan status quo. The more pressing questions are:

- Will NASA tilt further toward a SpaceX-centric architecture for launch, crew, and deep space missions?

- Can a NASA chief who is a private astronaut and investor in one major provider credibly act as an honest broker among competing firms?

- How will that shape America’s position in the global space race with China and others?

There are three plausible directions—none mutually exclusive.

1. NASA as Chief Integrator of a Commercial Constellation

Isaacman’s own flight history—Inspiration4 and Polaris Dawn—were flown on SpaceX hardware and marketed as proof that commercial missions can be technically sophisticated, safe, and emotionally resonant. That worldview naturally pushes NASA toward a role where it:

- focuses on systems integration, standards, safety, and science,

- lets companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and others handle more of the transport and infrastructure, and

- uses fixed-price, milestone-based contracts rather than traditional cost-plus arrangements.

In that scenario, NASA’s center of gravity shifts from owning hardware to owning the rules and the research. That can accelerate timelines and reduce costs, but it also risks making the agency dependent on a small number of ultra‑powerful contractors whose corporate priorities may not align with long‑term public interest, especially on issues like orbital congestion, debris, and military dual‑use technologies.

2. A Faster, Risk‑Tolerant Push to the Moon and Mars

Isaacman has been an outspoken advocate of Mars missions and has personally taken on high‑risk, high‑profile flights. Whether he intends to or not, his appointment sends a signal that risk tolerance is back in fashion at the top of NASA.

Historically, NASA has oscillated between daring and caution:

- Apollo accepted high levels of risk in a geopolitical race.

- Post‑Challenger and post‑Columbia NASA became more risk‑averse, with layers of bureaucracy designed to prevent catastrophes.

A private astronaut who has personally commanded missions may be more inclined to support aggressive schedules for Artemis landings and longer‑range Mars planning, seeing commercial rapid iteration as a model rather than a threat. That could mean:

- stronger support for Starship-based lunar and Mars architectures,

- pressure to streamline safety and procurement reviews to avoid “bureaucratic drag,” and

- a shift in how NASA communicates about risk to the public—less paternalistic, more aligned with the language of exploration and entrepreneurship.

3. A Test Case for Conflict‑of‑Interest Governance

Perhaps the most undercovered aspect of Isaacman’s appointment is what it means for governance. NASA already buys billions of dollars of services from companies in which Isaacman has both financial and reputational ties. While federal rules and ethics agreements can mandate recusals or divestiture, the perception of bias can be as damaging as the reality.

If Isaacman manages to navigate this cleanly—through transparent recusal policies, publicly disclosed ethics agreements, and demonstrably competitive procurement decisions—NASA could emerge as a model for how to manage billionaire‑government entanglements. If not, the agency risks a corrosive narrative: that federal space policy is being captured by a small club of interconnected elites whose private interests are inseparable from public decisions.

Global Stakes: NASA’s Role in a Crowded Space Race

Isaacman is taking over NASA as other powers are accelerating their own programs:

- China has landed on the far side of the Moon, built the Tiangong space station, and has announced ambitions for crewed lunar missions and resource extraction.

- India has achieved a successful lunar landing and is positioning itself as a cost‑effective space power.

- Europe, Japan, and others are deepening collaborations and refining their own commercial ecosystems.

In that context, a NASA administrator who is not just technocratically competent but deeply embedded in the commercial ecosystem could be an asset. He can potentially align NASA strategy with the most capable U.S. firms and move faster than agencies weighed down by legacy industrial structures.

But there’s a strategic trade‑off: the more NASA’s success is fused with one or two dominant companies, the more vulnerable U.S. space policy becomes to corporate shocks—technical failures, financial crises, or political controversies involving those firms or their leaders.

What Experts See Beneath the Headlines

Space policy experts and former officials are likely to see Isaacman’s confirmation as part of a longer arc rather than a rupture.

John Logsdon, a leading historian of U.S. space policy, has long argued that NASA’s survival depends on adapting to political realities and industry structure. In this case, adaptation means embracing the commercial ecosystem that now outpaces traditional government programs in innovation and speed.

But others warn about the institutional costs. Former NASA officials have quietly raised concerns for years about “vendor capture,” where the agency’s internal culture, workforce planning, and program designs are increasingly optimized around a small number of providers.

Ethics scholars also point to a broader U.S. trend: the rise of billionaire “policy shapers” whose philanthropic and business activities intersect with government roles, from education and health to climate and now space. Isaacman’s NASA will be an important test case of whether that model can be squared with traditional expectations of public accountability.

The Overlooked Story: Space as Domestic Political Currency

Mainstream coverage has focused on the personal saga—feud, withdrawal, reconciliation, confirmation. What’s less discussed is how space policy itself has become a domestic political currency.

Trump’s public jousting with Musk, followed by Musk’s reported financial support for Republican candidates, and the rehabilitation of a Musk‑aligned NASA nominee, illustrates how space has been integrated into broader ideological and donor networks. This isn’t unprecedented—defense and energy policy have long been politicized—but it represents a shift for a domain that for decades enjoyed relatively stable bipartisan insulation.

The risk is that long‑term programs like Artemis or Mars planning—which span multiple administrations and budget cycles—become collateral damage when political alliances shift. A NASA leadership aligned too closely with one faction or donor network can find its projects under threat if that faction loses influence.

What to Watch Next

The real impact of Isaacman’s tenure won’t be visible in a week of headlines. It will emerge over the next 2–5 years. Key markers to watch include:

- Ethics and disclosure: Does NASA publish detailed information on Isaacman’s financial ties and recusal policies? Are there visible steps to diversify major contract awards?

- Artemis architecture choices: Do timelines and funding decisions clearly favor architectures where SpaceX plays the central role, or is there an effort to broaden participation?

- Risk posture: Do human spaceflight and Mars‑related programs adopt more aggressive timelines and accept higher levels of technical risk?

- International collaboration: Does Isaacman deepen partnerships with allies, or does a commercial‑first posture push NASA toward more transactional arrangements?

- Workforce and culture: How does NASA’s civil‑service workforce respond to leadership from a private astronaut? Are there shifts in internal priorities away from in‑house engineering toward program management and oversight?

The Bottom Line

Jared Isaacman’s confirmation as NASA administrator is not just the epilogue to a Trump–Musk feud. It is the institutionalization of a new model of U.S. space power: publicly funded, commercially executed, and increasingly shaped by the decisions of a small number of billionaire‑entrepreneurs and their political allies.

If managed well, Isaacman’s tenure could accelerate lunar and Mars exploration, strengthen U.S. leadership in an intensely competitive global space race, and demonstrate how government can harness private innovation without surrendering the public interest. If mismanaged, it risks deepening public skepticism about conflicts of interest, narrowing the competitive field, and turning NASA into another arena where partisan and donor politics override long‑term scientific and strategic goals.

Either way, this appointment marks a turning point: the era when NASA could pretend to stand apart from the politics and power struggles of the 21st‑century space economy is over.

Topics

Editor's Comments

What’s striking in the Isaacman confirmation is how normalized billionaire-led governance of public functions has become. A decade ago, the mere idea of a NASA chief with deep financial and operational ties to one dominant contractor would have generated sustained scrutiny; now, it passes with a solid bipartisan vote and relatively narrow debate about ethics. That reflects two converging trends: the hollowing out of the federal government’s in-house technical capacity and the political system’s growing dependence on mega-donors whose business empires increasingly overlap with public infrastructure. The unresolved question is whether our oversight mechanisms—ethics agreements, congressional hearings, inspector general reviews—are robust enough for an era in which individuals like Isaacman and Musk sit at the intersection of private capital, national prestige, and strategic competition with China. If they aren’t, we may be sleepwalking into a model where critical public choices are driven less by deliberation and more by the balance of power within a very small, very wealthy club.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.