Behind the Bench: What Minnesota’s Overturned $7.2M Fraud Verdict Reveals About the Future of White-Collar Prosecutions

Sarah Johnson

December 14, 2025

Brief

An in-depth look at Judge Sarah West’s reversal of a $7.2M Medicaid fraud conviction in Minnesota, unpacking the state’s strict circumstantial evidence rule, political fallout, and implications for future white-collar cases.

Minnesota’s ‘Highly Unusual’ Fraud Ruling Isn’t Just About One Case. It’s About the Future of White-Collar Prosecutions.

The uproar over Judge Sarah West’s decision to overturn a $7.2 million Medicaid fraud conviction is being framed as a story about one judge and one defendant. In reality, it sits at the intersection of three much bigger battles: how we define proof in complex financial crimes, how courts respond to massive welfare fraud scandals, and how politics weaponizes public distrust in the justice system.

To understand what’s really at stake, you have to look beyond the headlines and into the structural tension between jury power, judicial oversight, and a legal standard for circumstantial evidence that is arguably out of step with national practice.

Why This Case Matters Far Beyond Minnesota

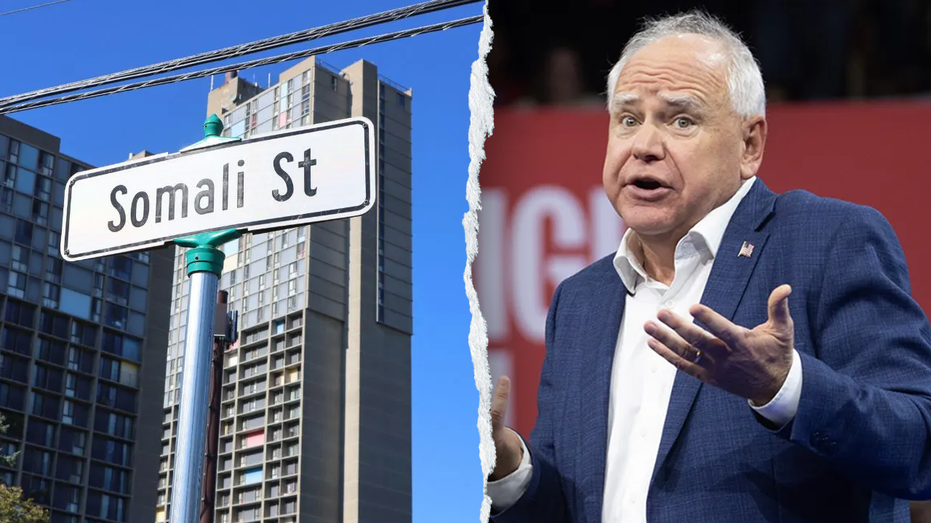

On its face, the case is straightforward: a Minnesota jury unanimously convicted Abdifatah Yusuf on six counts of aiding and abetting theft for allegedly siphoning $7.2 million from the state’s Medicaid program through a home healthcare business that prosecutors described as essentially a shell, run out of a mailbox and used to fund a luxury lifestyle.

Then Judge West did something that is both legally permissible and politically explosive: she tossed the verdict after trial, ruling the evidence was circumstantial and did not eliminate a reasonable alternative — that Yusuf owned the business, but his brother may have committed the fraud without his knowledge.

That move struck at the heart of three deeply contested arenas:

- The standard of proof in white-collar crime — where intent is almost always inferred rather than directly observed.

- The balance of power between judge and jury — especially when public anger over fraud is running hot.

- The politicization of welfare fraud — particularly in Minnesota, where human services fraud involving immigrant communities is already a flashpoint.

It’s not just a question of whether one defendant walks free. It’s about whether Minnesota will remain one of the hardest states in the country to secure and keep a conviction in complex financial cases — and what that means for billions in taxpayer-funded programs.

The Bigger Picture: A Strict Evidence Rule Built for a Different Era

The most important fact in this story isn’t the dollar amount or even the judge’s background. It’s Minnesota’s unusually strict rule for circumstantial evidence in criminal cases.

For decades, Minnesota has applied a doctrine that goes beyond the federal standard and most states: when a conviction rests primarily on circumstantial evidence, prosecutors must exclude every reasonable hypothesis of innocence. If another reasonable explanation for the defendant’s conduct exists, the conviction can’t stand.

This doctrine dates back to an era when courts viewed circumstantial cases with heightened suspicion, fearing that inferences could be stacked on inferences until a narrative felt persuasive but was not objectively proven. Many jurisdictions have since moved away from this test, relying instead on a more unified standard: would any rational juror, viewing the evidence as a whole, find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt?

Minnesota has largely stuck with the older approach, and that decision is now colliding with the reality of 21st-century fraud. Modern white-collar and welfare schemes often involve:

- Complex billing systems rather than direct eyewitnesses

- Layers of ownership and management across family members or associates

- Electronic paper trails that show what happened, but not always who intended what

In that environment, demanding prosecutors negate every reasonable alternate scenario can make high-dollar fraud cases fragile on appeal, even when the factual pattern looks damning to a jury.

That’s the legal backdrop Judge West is operating in. As Professor JaneAnne Murray notes, she was applying the law as it stands. The controversy arises because that law is itself under review by the Minnesota Supreme Court — and because the public mood, after massive welfare scandals, is in no mood for nuance.

Juries, Judges, and the Quiet Battle Over Who Gets the Last Word

Overturning a jury verdict in a criminal case is rare not because courts lack the power, but because doing so cuts against one of the strongest norms in American law: deference to the judgment of a jury of peers.

In most jurisdictions, judges can set aside a guilty verdict only if no reasonable jury could have reached it based on the evidence. That threshold is intentionally high; otherwise, bench oversight can morph into substitution of judgment. Andy McCarthy’s criticism taps into this worry: if circumstantial evidence is categorically discounted, he argues, many legitimate convictions will never survive a skeptical trial judge.

But Minnesota’s circumstantial-evidence doctrine effectively invites judges to re-examine not just whether the evidence could support guilt, but whether it adequately excludes innocence. In practice, that means:

- Juries can find a defendant guilty based on a strong narrative of involvement.

- Judges can later say that narrative is not the only reasonable one and set aside the verdict.

That is precisely what happened here. West accepted that Yusuf was the owner of the company and that large-scale fraud occurred. But she concluded that a reasonable person could believe his brother was the architect of the scheme and that ownership alone, plus lifestyle evidence, wasn’t enough to prove knowledge beyond a reasonable doubt.

This raises a deeper question: in complex financial crimes, where direct admissions or eyewitnesses are rare, how much weight should courts give to circumstantial patterns — like lavish spending, dummy offices, and suspicious billing — as proof of intent?

Fraud, Trust, and the Politics of Welfare Scandals

This decision doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Minnesota is already under intense scrutiny for its oversight of human services programs, with reported fraud totals approaching or exceeding $1 billion in recent years across various schemes.

That environment matters for three reasons:

- Public trust is fragile. When taxpayers see luxury cars, designer goods, and multimillion-dollar thefts tied to welfare programs, they are far less tolerant of legal technicalities that appear to let alleged offenders off the hook.

- Political actors see opportunity. Republicans have leveraged these scandals to attack DFL leadership, including Gov. Tim Walz, as soft on fraud and mismanaging welfare programs. West’s ruling becomes more than a judicial decision; it becomes evidence in a partisan narrative.

- Community tensions are heightened. Some of the largest fraud cases have involved members of Minnesota’s Somali community. That reality feeds sensitive debates about immigrant integration, oversight, and prejudice, even when not stated explicitly.

Labeling Judge West a “true extremist,” as one GOP state senator reportedly did, isn’t just rhetorical flair; it’s part of a broader effort to frame the judiciary as an obstacle to accountability in welfare fraud. That framing can be politically powerful but legally distorting, pressuring judges to respond not only to the law, but to the court of public opinion.

What’s Being Overlooked: Transparency and the Sealed Record

One underreported dimension of this fight is the dispute over access to the case record. Sen. Michael Holmstrom’s demand that exhibits and the case file be unsealed touches a core principle: a justice system’s legitimacy depends on its openness.

If critical evidence, arguments, or reasoning remain sealed, it becomes far harder for the public — or independent legal analysts — to assess whether West’s ruling was a principled application of a strict standard or an overreach that undermines the jury’s role. In a high-stakes public fraud case, sealing large portions of the record is almost guaranteed to fuel suspicion, regardless of the legal justification.

That creates a dangerous feedback loop:

- Fraud scandals erode trust in public institutions.

- Controversial court decisions deepen skepticism.

- Secrecy, even if legally justified, appears like a cover-up.

The long-term risk is not just cynicism about one judge, but a broader collapse of confidence in Minnesota’s ability to investigate, try, and transparently adjudicate complex fraud cases.

Data and National Context: How Unusual Is This, Really?

Empirical data on post-verdict acquittals is limited, but studies of federal and state courts suggest that trial judges rarely set aside criminal jury verdicts on sufficiency grounds. In many jurisdictions, such rulings are counted in the low single digits annually.

By contrast:

- The vast majority of fraud cases end in plea bargains, never reaching a jury.

- Among the small percentage that go to trial, appellate courts — not trial judges — are the more common venue for challenging evidentiary sufficiency.

So West’s decision is statistically unusual, but it’s not lawless. It is, instead, a product of Minnesota’s unique doctrinal posture toward circumstantial evidence. If this case is overturned on appeal, it could signal that even within that framework, higher courts think trial judges are reading the standard too aggressively. If it’s upheld, it may force prosecutors to fundamentally rethink how they build circumstantial cases.

Expert Perspectives: Intent, Evidence, and Judicial Restraint

Legal scholars and practitioners are split, often along lines of what they fear most: wrongful conviction or under-enforcement of complex crimes.

Those focused on civil liberties argue that the power to imprison should be checked aggressively when intent is inferred from financial patterns and lifestyle choices. They note that owning a business where fraud occurs, or spending large sums of money, is not by itself definitive proof of criminal intent.

Prosecutors and many former federal attorneys counter that in sophisticated fraud schemes, the “smoking gun” almost never exists. Email admissions, recorded confessions, or eyewitnesses to planning meetings are the exception, not the rule. If courts demand proof that is rarely available in the real world of white-collar crime, they argue, large-scale theft from the public will go unpunished.

This isn’t just a philosophical divide. It’s a practical one: how much risk of wrongful conviction are we willing to tolerate in order to deter and punish complex fraud, and vice versa?

Looking Ahead: What This Case Could Change

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison has already appealed West’s decision. The outcome could reshape several key areas:

- The circumstantial evidence standard itself. If the Minnesota Supreme Court narrows or abandons the “exclude every reasonable hypothesis of innocence” rule, future fraud prosecutions will become easier to sustain, and trial judges will have less room to overturn jury decisions.

- Charging strategies in fraud cases. Prosecutors may increasingly focus on individuals closest to transactional details — the people signing claims, sending emails, or directing staff — rather than higher-level owners whose involvement is more inferential.

- Judicial appointments and elections. This case will almost certainly be used in future political campaigns and judicial evaluations, especially for judges perceived as defense-oriented or skeptical of circumstantial cases.

- Transparency and court procedures. Legislative or rule changes may emerge to limit sealing in high-profile public fraud cases, or at least to require more detailed public explanations when records are restricted.

Beyond Minnesota, other states grappling with large-scale COVID-relief fraud, Medicaid abuse, and nonprofit scams will be watching. As public demand for accountability grows, appellate courts nationwide will face similar tensions: how far can you stretch inferences from money flows and lifestyle evidence before you risk criminalizing association and ownership rather than proven intent?

The Bottom Line

Judge West’s decision isn’t simply an outlier in a single Medicaid fraud case. It’s a stress test of how our justice system handles complex, paper-based crimes at a time of intense public anger over welfare fraud.

If the ruling stands, it will reinforce Minnesota’s status as one of the most demanding jurisdictions for circumstantial fraud cases and may embolden judges to more aggressively police sufficiency of evidence. If it falls, it may mark the beginning of the end for a decades-old doctrine that critics say is ill-suited to modern financial crime.

Either way, the fundamental question remains unsettled: in a world where intent is rarely captured on tape, how much circumstantial evidence is enough to send someone to prison for stealing from the public — and who gets the final say when a jury and a judge disagree?

Topics

Editor's Comments

What’s striking in this case is how little of the public debate grapples with the core legal question: do we want a system that maximizes deference to juries, or one that aggressively guards against the risk of convicting someone based on ambiguous financial patterns? Minnesota’s circumstantial evidence standard represents an explicit choice in favor of the latter, but that choice was made in a very different fraud environment. Today’s large-scale welfare schemes are diffuse, tech-enabled, and often shielded through family or community networks. That creates a genuine policy problem: if courts cling to evidentiary doctrines that demand near-perfect clarity of intent, the law may lag too far behind the realities of modern fraud. At the same time, relaxing safeguards risks normalizing convictions built on stereotypes about who looks like a fraudster — immigrants, business owners in certain sectors, or people with conspicuous wealth. The appellate courts are not just reviewing one judge here; they are being asked to recalibrate a balance between security and liberty that will shape every major fraud case Minnesota brings in the next decade.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.