Beyond the Headlines: How Fear of Racism Claims Helped Fuel Minnesota’s Feeding Our Future Fraud Explosion

Sarah Johnson

December 14, 2025

Brief

An in-depth analysis of Minnesota’s Feeding Our Future scandal, showing how fear of racism accusations, weak oversight, and electoral politics enabled massive fraud and what reforms are needed to protect both equity and accountability.

Minnesota’s Feeding Our Future Scandal: How Weaponized Identity Politics Collided With Weak Oversight

At first glance, the Feeding Our Future scandal looks like a familiar fraud story: opportunists exploiting a loosely monitored federal nutrition program and weak state oversight to siphon off staggering sums of public money. But the deeper story is far more consequential. In Minnesota, the fear of being labeled “racist” did not just chill political and media scrutiny; it interacted with structural oversight failures, intense demographic politics, and an under-resourced compliance system to create what prosecutors describe as one of the largest pandemic-era fraud cases in the country.

This scandal is not just about one nonprofit or one immigrant community. It exposes a national dilemma: how to protect vulnerable populations and support minority-led organizations without turning legitimate concerns about racial bias into a blanket shield against accountability. If Minnesota is a warning, it’s that when identity politics and patronage intersect with huge, fast-moving federal dollars, the cost is paid twice—first by taxpayers, and then by the very communities these programs are supposed to serve.

The Bigger Picture: How We Got Here

To understand why accusations of racism became such a powerful deterrent to oversight, we need to place this scandal in at least three broader contexts:

1. A long history of racial inequity in public programs

American social programs have a well-documented history of discriminatory application—everything from redlining to biased welfare enforcement. Minority and immigrant communities often have been disproportionately scrutinized or stigmatized as “fraud risks.” That history creates an understandable sensitivity: when agencies suddenly crack down on fraud in a predominantly Somali network of providers, community leaders are primed to ask whether it’s race-driven.

In Minnesota, Somali refugees and immigrants, many escaping civil war, have spent decades fighting stereotypes: about Islam, about refugees and about perceived “abuse” of welfare programs. That background makes claims of selective enforcement emotionally resonant—even when systemic fraud is clearly present.

2. Pandemic-era money with pre-pandemic guardrails

The Feeding Our Future case unfolded under the umbrella of federal child nutrition programs during COVID-19, when Washington dramatically expanded funding and loosened requirements to stave off hunger. Nationally, the Government Accountability Office has flagged that these emergency flexibilities multiplied fraud risks across programs like unemployment insurance and PPP loans. Minnesota wasn’t unique in having money outpace oversight, but it was unusual in how large, concentrated and politically sensitive the alleged fraud became.

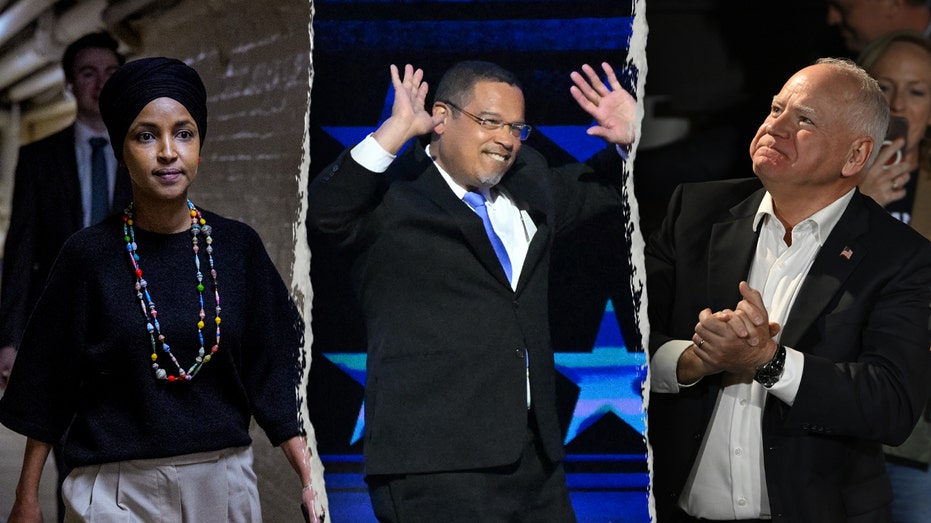

3. The political rise of the Somali vote in Minnesota

Minnesota’s Somali community has become a crucial voting bloc, particularly in parts of Minneapolis and in the congressional district represented by Rep. Ilhan Omar. Close statewide races and competitive Democratic primaries magnify the value of this largely Democratic-leaning constituency. That reality doesn’t cause fraud, but it changes incentives. When community intermediaries are gatekeepers to a vital vote, politicians may be more cautious about crossing them—even when red flags emerge.

Put those three forces together—historic discrimination, weak pandemic-era guardrails and concentrated electoral power—and you get an environment where allegations of racism are not just morally charged but politically explosive. That’s the context in which regulators and politicians hesitated, and fraudsters, as federal prosecutors allege, learned to weaponize that hesitation.

What This Really Means: When Identity Becomes Legal Armor

The central allegation emerging from investigators and former prosecutors is not simply that people cried racism, but that the mere threat of that label altered institutional behavior. That distinction is crucial.

According to the legislative auditor’s report and those quoted in the story, officials at Minnesota’s Department of Education believed they needed to handle Feeding Our Future “carefully” because of racism accusations and media risk. That isn’t passive context—it’s a direct line between reputational fear and regulatory restraint.

The implications run much deeper than one scandal:

- Regulators became risk-averse about enforcing the rules exactly where enforcement was most needed. When enforcement in minority communities carries a higher reputational cost than enforcement elsewhere, then by definition we’re not applying equal protection under the law.

- Racial justice language was co-opted. When suspects allegedly tell the state attorney general that they are being investigated “only because of race,” they are borrowing vocabulary developed to confront systemic discrimination and repurposing it as a defensive tactic against criminal prosecution.

- Public trust—already fragile—takes a double hit. Many Somali Minnesotans who run legitimate childcare, food and social service operations now face greater suspicion because high-profile fraud went unaddressed for so long. Meanwhile, other Minnesotans see the scandal as proof that “political correctness” has gone off the rails. Both mistrusts are rooted in real institutional failure.

This is the paradox: by treating accusations of racism as career-ending landmines instead of serious claims to investigate on the merits, institutions can actually make racial equity harder to achieve. When everything is untouchable, nothing is protected.

Expert Perspectives: The Structural Issues Behind the Scandal

Experts in public administration, anti-corruption and race politics see patterns that go beyond Minnesota.

On the misuse of anti-racism language

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a leading scholar of critical race theory, has long argued that anti-racist frameworks are designed to illuminate structural inequality, not shield individuals from any scrutiny. When accusations of racism are used primarily as a litigation or PR tactic, they risk diluting the moral force of real discrimination claims.

On enforcement chilling effects

Former federal inspector general Michael Horowitz has warned that agencies often overcorrect in response to political pressure—tightening or loosening enforcement along lines that track media narratives more than risk assessments. In Minnesota, the sequence—initial red flags, accusations of racial targeting, a lawsuit, then resumed payments without deeper investigation—fits that pattern.

On the electoral dimension

Political scientists who study ethnic bloc voting note that as concentrated immigrant communities gain electoral leverage, local politics often shift toward patronage and community brokers. When nonprofit networks become intertwined with political mobilization, the line between constituent service and clientelism can blur. That doesn’t mean fraud is inevitable, but it raises the stakes when those networks are scrutinized.

Data & Evidence: How Big Is the Problem?

The numbers in this case are eye-popping but also fit a wider pattern of pandemic-era fraud:

- Federal authorities have said the Feeding Our Future case involves around $250 million in alleged fraud through child nutrition programs, though some Minnesota officials suggest broader state program losses could reach into the billions annually when including other schemes and inefficiencies.

- Nationally, the Department of Labor estimates that more than $100 billion may have been stolen from pandemic unemployment relief alone. The Small Business Administration has similarly flagged tens of billions in potentially fraudulent PPP and EIDL loans.

- Legislative audits in multiple states—from California to New York—have found that rapid program expansion, streamlined verification and weak inter-agency data sharing were common vulnerabilities.

What distinguishes Minnesota is less the scale of loss than the specific mechanism of delay: the documented institutional fear of racial accusations as a factor in enforcement decisions, and the alleged explicit invocation of race by some suspects.

What’s Being Overlooked: The Victims Inside the Community

Much of the political conversation has focused on taxpayers and partisan blame. Far less attention has gone to the Somali families and other low-income households who should have benefited from these nutrition and autism services—and often didn’t.

When fraudsters bill the state for non-existent meals or inflated service hours, three things happen:

- Money that could expand legitimate programs instead funds luxury cars, properties or overseas transfers, as alleged in indictments.

- Future funding comes under suspicion, making it harder for honest community organizations—often led by the same minority communities—to access grants.

- Entire neighborhoods get stigmatized as “fraud hotbeds,” reinforcing the very stereotypes that anti-racism efforts are meant to dismantle.

In interviews across similar scandals, social workers and community advocates often describe a painful split: many in the community quietly know when a program is a sham, but fear of being seen as disloyal—or of feeding anti-immigrant sentiment—keeps them silent. That dynamic appears to have been at play in Minnesota, where rumors of fraud reportedly circulated for years.

Looking Ahead: How to Protect Both Equity and Accountability

The Minnesota scandal underscores that the binary “fight fraud” versus “fight racism” is a false choice. Effective governance has to do both simultaneously. Several reforms emerge as critical:

- Build race-neutral, risk-based enforcement frameworks. Agencies should rely on transparent, data-driven models that flag irregularities—volumes, cost patterns, participation rates—regardless of the demographic makeup of providers. When people cry discrimination, officials can point to clear, published criteria.

- Create an independent channel for reviewing racism allegations related to enforcement actions. Instead of regulators backing off at the first accusation, there should be a structured process—potentially involving a civil rights or ombudsman office—to quickly assess whether an investigation is biased. If it isn’t, the investigation continues with added transparency.

- Separate political calculus from program oversight. Governors and legislators with subpoena power or budget authority should be required to document—and publicly disclose—why they did or did not act on major fraud warnings, especially when they involve politically sensitive communities.

- Strengthen protections for whistleblowers inside communities. Outreach in multiple languages, anonymous reporting tools and partnerships with trusted local leaders can make it easier for people to report fraud without feeling they’re betraying their community.

- Train media and public officials on distinguishing between patterns and prejudices. Reporting on fraud within a specific ethnic network is not inherently racist. It becomes racist when it extrapolates from individual wrongdoing to the inherent nature of a group. That nuance should be central to newsroom and agency training.

Some of these reforms are already being discussed in Minnesota, but they will only matter if the state internalizes the core lesson: the fear of being labeled racist cannot be allowed to operate as an informal veto on oversight.

The Bottom Line

The Feeding Our Future scandal is not just a story of greedy actors gaming a generous system. It’s a case study in how institutions can be paralyzed when legitimate concerns about racism and xenophobia are treated as political hazards to be avoided rather than issues to be examined and addressed alongside fraud.

If Minnesota responds by building stronger, more transparent, race-conscious and race-neutral safeguards, it could turn a multibillion-dollar failure into a national blueprint. If, instead, the scandal is reduced to another partisan talking point about “soft-on-fraud Democrats” or “anti-immigrant witch hunts,” the underlying vulnerabilities—in oversight, in political incentives, and in how we discuss race and accountability—will remain wide open for the next crisis.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One uncomfortable but necessary angle here is the role of elite gatekeepers—both political and media—in turning a legitimate concern about racism into a de facto liability rule: if a case involves a marginalized community, touching it becomes riskier than leaving it alone. That calculus is rational in a narrow career sense; nobody wants to be the next viral villain in a social media pile-on. But it’s disastrous as a public governance principle. What stands out in the Minnesota scandal is not only the alleged cynicism of some fraudsters, but the institutional unwillingness to build robust channels for handling racism claims and fraud claims at the same time. Instead of investing early in processes that can discriminate between bias and accountability, leaders punted until the problem metastasized and the political costs skyrocketed. The contrarian takeaway is that the safest path for both communities and officials is actually more confrontation with hard questions about race and enforcement, not less—so those questions are resolved in real time, rather than after a billion-dollar failure.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.