Beyond the Booth: What Cris Collinsworth’s Comments Reveal About the NFL’s Mental Health Blind Spot

Sarah Johnson

December 16, 2025

Brief

Cris Collinsworth’s comments about Marshawn Kneeland’s suicide expose deeper failures in how the NFL and its broadcasters handle mental health, tragedy, and trauma in a league built around entertainment.

Note: This analysis discusses suicide and mental health in professional sports. If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 in the U.S.

Why this broadcast moment matters

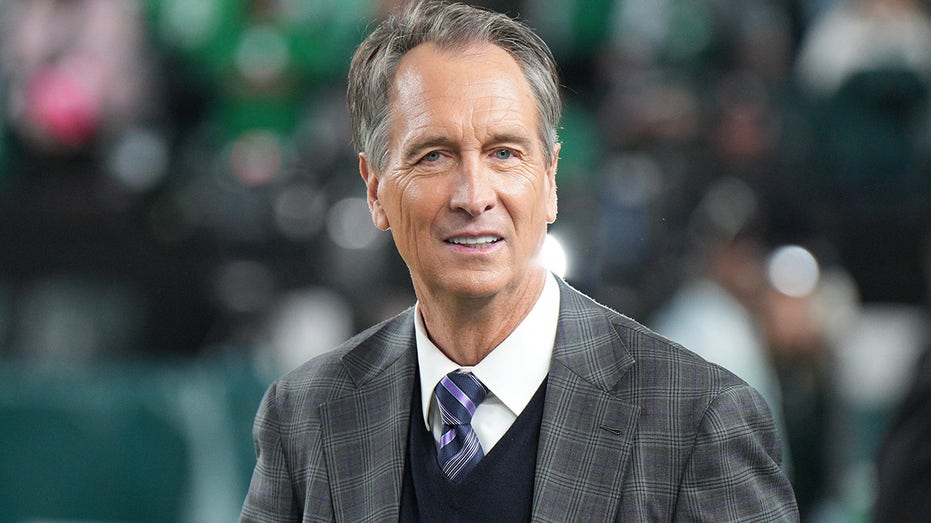

Cris Collinsworth’s on-air references to Dallas Cowboys lineman Marshawn Kneeland’s suicide are not just a question of one commentator’s judgment. They expose a deeper struggle in American sports media: how to cover trauma, mental health, and death in real time, in a business built around entertainment, ratings, and narrative drama. What played out Sunday night wasn’t simply a misstep; it was a collision between three powerful forces—NFL culture, broadcast incentives, and evolving norms around mental health—and the fallout tells us where those tensions are still unresolved.

Collinsworth’s remarks drew swift criticism because they seemed to link a young player’s death to a broader storyline about the Cowboys’ season and roster decisions, including Micah Parsons’ trade. That framing—intentional or not—felt to many fans like emotional exploitation: turning an individual tragedy into a plot point.

To understand why this struck such a nerve, we have to zoom out: how sports media has historically handled death, how mental health has been framed in the NFL, and why broadcasters remain unprepared for the ethical demands of a post-CTE, post-pandemic mental health landscape.

How sports media has handled tragedy: from silence to spectacle

For decades, major U.S. sports broadcasts largely avoided deep engagement with mental health and suicide. The playbook was familiar: acknowledge the death briefly, offer condolences, then move back to the game. The implicit rule: don’t linger, don’t complicate, don’t disrupt the product.

When tragedies did force themselves into the broadcast—such as the sudden deaths of athletes or high-profile incidents—coverage often swung between two extremes:

- Sanitized euphemism – deaths framed in vague terms, with causes obscured or described as “personal issues” or “off-field challenges.”

- Emotional spectacle – extended montages, dramatic narratives, and commentary that subtly turned tragedy into a storyline, sometimes romanticizing pain or perseverance.

In football specifically, major turning points like the concussion crisis and the suicides of former players (e.g., Junior Seau in 2012, Dave Duerson in 2011) forced the league and its media partners to acknowledge brain injury and mental health more directly. Yet even then, coverage often focused on legal liability and medical controversies more than the day-to-day psychological reality of players.

What’s changed in the last five to ten years is the cultural context. Younger fans are far more attuned to mental health, trauma, and responsible language about suicide. Social media gives them a direct channel to call out coverage in real time. A commentary style that might have passed unchallenged in the 1990s now triggers an immediate, public accountability mechanism.

What Collinsworth’s comments reveal about the broadcast mindset

By bringing up Kneeland’s suicide multiple times and tying it to the Cowboys’ struggles and roster decisions, Collinsworth was doing what football broadcasters are trained to do: build a coherent narrative. Every season becomes a story arc—adversity, conflict, resilience, redemption. The problem is that not every real-world event belongs in that arc.

There are three specific issues embedded in his approach:

- Conflating tragedy with performance. When a player’s death is framed alongside trades, injuries, and poor play, it risks reducing a human life to a factor in a team’s fortunes. The ethical line is crossed when suicide becomes part of the dramatic scaffolding of a season.

- Lack of trauma-informed practice. Modern journalism increasingly embraces trauma-informed reporting—avoiding gratuitous detail, not speculating on motives, and not repeatedly invoking suicide in ways that can be triggering. Most live sports booths have not caught up with those standards.

- Audience as a moral check. The speed and intensity of fan backlash reflect a shift: viewers no longer see themselves only as consumers of a product. They see themselves as stakeholder-participants who can and should push back when coverage feels exploitative or insensitive.

The NFL’s mental health paradox

Kneeland’s death sits at the intersection of several longstanding fault lines within the NFL:

- Hyper-masculine culture. The league has historically valorized toughness, stoicism, and playing through pain. That culture can make it harder for players to seek help for depression, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts.

- Real progress, unevenly implemented. The NFL has, in recent years, expanded mental health resources, adding mandated behavioral health professionals for each team and public campaigns about mental wellness. But stigma, fear of losing playing time, and distrust of team-controlled resources often blunt their impact.

- Violence, trauma, and identity loss. Professional football combines physical trauma (including possible brain injury), intense public scrutiny, job insecurity, and a fragile sense of identity tied to performance. For a young player like Kneeland—new to the league, recently drafted, still navigating expectations—the pressures are enormous.

When broadcasters mention suicides in this context without grappling with these systemic pressures, they unintentionally reinforce the idea that such deaths are isolated tragedies, not signals of deeper institutional problems.

How suicide is (and isn’t) supposed to be covered

Public health research and journalistic ethics provide fairly clear guidelines on suicide coverage:

- Avoid describing specific methods or graphic details.

- Don’t oversimplify causes (“it was because of the season” or “a bad game”).

- Don’t frame suicide as inevitable or as a rational response to hardship.

- Do provide resources and emphasize that help is available.

- Do treat the person as more than their death, acknowledging their life and humanity.

Sports booths, built around banter, quick pivots, and storytelling, aren’t currently designed to follow these standards in live, unscripted moments. That’s not an excuse; it’s an indictment of how slowly broadcast institutions have adapted. The same production teams that spend hours on officiating rules and replay protocols rarely invest similar time in training for mental health or trauma coverage.

Expert insight: where the line was crossed

Sports psychiatrist Dr. Daniel Eisenberg, who has consulted with college and professional teams, explained in a recent panel discussion on media and athlete mental health:

“The key issue is framing. When suicide is presented as part of a narrative about winning, losing, or team adversity, it subtly suggests that the value of a life is measured in its impact on a season. That’s where ethical coverage breaks down.”

Media ethicist Kelly McBride has similarly argued that in live broadcasts, the most responsible approach is often minimalism: acknowledge the tragedy with care, don’t speculate, and avoid integrating it into game analysis unless there is a clear, respectful reason to do so.

What mainstream coverage is missing

Most reactions to Collinsworth have focused on whether he was “insensitive,” whether he should apologize, or whether he should face discipline. That’s the familiar accountability script—personalize the problem, then solve it by punishing or shaming one individual.

What’s largely missing is the structural critique:

- No shared standards. Unlike hard news operations, sports broadcast teams often lack detailed internal guidelines for discussing suicide, mental health, or traumatic events in real time.

- No visible mental health expertise in the booth. Analysts and play-by-play commentators are chosen for football knowledge and on-air presence, not for their ability to navigate psychological or ethical complexity.

- Ratings pressures. Networks reward emotionally resonant narratives that keep viewers engaged. That incentive doesn’t disappear when the topic is tragedy; it sometimes intensifies.

Focusing solely on Collinsworth obscures the broader question: why was he left to improvise in such a fraught area without visible guardrails?

Data points: athlete mental health risks are not hypothetical

Several trends make careful coverage more urgent:

- Research in sports psychiatry has found elevated rates of depression and anxiety among elite athletes compared with the general population, despite high income and status.

- A 2019 study published in JAMA Neurology reported that over 90% of former NFL players studied posthumously had signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a condition associated with mood disorders, impulsivity, and suicidal behavior.

- Active and recently retired NFL players have, in the last decade, increasingly spoken openly about suicidal ideation and severe depression, including Brandon Marshall and Dak Prescott, signaling that these issues are neither rare nor fringe.

Against that backdrop, references to a player’s suicide during a game broadcast cannot be treated as incidental color—they unfold in a landscape where other players, coaches, and viewers may be personally at risk.

What needs to change: from crisis reaction to ethical infrastructure

If this controversy is to mean more than a news cycle of outrage, several concrete shifts are needed:

- Formal guidelines for live sports coverage.

Networks and leagues should jointly develop and publish clear standards for discussing suicide, violence, and severe mental health crises on air, modeled on best practices from public health and trauma journalism. - Mandatory training for on-air talent and producers.

Just as broadcasters are trained on replay rules and gambling disclosures, they should receive regular training on mental health language, suicide contagion risk, and trauma sensitivity. - Reframing the role of the booth.

Commentators should be empowered—and expected—to say less in situations where they lack expertise, and to defer to prepared statements or mental health professionals where appropriate. - Integrating mental health into the broader football conversation.

Responsible coverage doesn’t mean never mentioning suicide; it means placing it in a context that acknowledges systemic pressures and available support rather than treating it as a plot twist.

Looking ahead: why this won’t be the last flashpoint

Given the physical and psychological stakes of modern football, the NFL and its media partners will face more—not fewer—situations involving mental health crises, deaths, and traumatic events, whether on or off the field. The question is whether they will continue to improvise, or build a durable ethical framework.

Several indicators to watch:

- Network response. Does the network behind the broadcast issue internal guidance, public standards, or on-air acknowledgment of how it will handle similar situations in the future?

- League involvement. Does the NFL treat media coverage of player mental health as part of its duty of care, or as a purely external matter?

- Player and union voices. Do current players or the NFLPA begin calling for better media standards around mental health and tragedy, framing this as an occupational safety issue rather than PR?

The human core: remembering Marshawn Kneeland

Lost amid the broadcast criticism is the person at the center of this story. Marshawn Kneeland was not primarily a plot point in the Cowboys’ season. He was a 24-year-old athlete who had just scored his first NFL touchdown, recently drafted out of Western Michigan, with a long career seemingly ahead of him.

Ethical coverage of his death requires holding two truths at once: that his suicide is part of a wider mental health crisis in high-pressure sports, and that his life cannot be reduced to that crisis. When broadcasters and media fail on either front—by avoiding the topic entirely or by subsuming it into a narrative about wins and losses—they miss the point.

The bottom line

The backlash to Cris Collinsworth is about more than one commentator’s judgment. It’s a referendum on how American sports media handles grief, mental illness, and death in an industry built on spectacle. If there is any constructive outcome to this moment, it will be measured not in apologies, but in whether the next tragedy is met with something more than improvisation: clear standards, better training, and a recognition that some stories demand we step out of the entertainment script altogether.

Topics

Editor's Comments

What’s most striking about this controversy is how much of the public conversation has focused on whether Cris Collinsworth is a villain or simply ‘out of touch,’ while almost no one is asking why a billion-dollar broadcast operation still relies on ad hoc judgment when discussing suicide on air. We have normalized the idea that sports booths are places for improvisation and personality, but not for rigorous ethical standards, even as the topics they confront—brain injury, domestic violence, mental illness, death—have grown more serious. In that sense, Collinsworth is less the cause than the symptom of a system that hasn’t caught up with the stakes of its own storytelling. The more uncomfortable but necessary question is whether networks and leagues are willing to sacrifice a bit of narrative drama and spontaneity to build structures—training, guidelines, expert input—that treat players and viewers as humans first and content second.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.