Beyond Outrage: How the Charlie Kirk Backlash Is Normalizing Talk Around Political Violence

Sarah Johnson

December 15, 2025

Brief

Jennifer Welch’s remarks about Charlie Kirk expose a deeper crisis: how outrage media, identity politics, and partisan incentives are normalizing rhetorical proximity to political violence in American life.

When Political Violence Becomes Content: What the Charlie Kirk Backlash Reveals About a Broken Culture

The argument over whether Jennifer Welch "justified" Charlie Kirk’s assassination isn’t really about one podcaster, one widow, or one conservative commentator. It’s about something far more unsettling: how a culture saturated with polarization, performative outrage, and social media incentives is steadily normalizing rhetorical proximity to political violence.

In this episode of the post-assassination fallout, a far-left podcast host says Kirk "justified" his own killing because of his pro–Second Amendment stance. A grieving widow is accused of being a "grifter" and a "disgrace." A former cable news anchor suggests her grief seems "acty," while insisting he’s not happy Kirk is dead but understands why marginalized people feel the way they do. Meanwhile, students are filmed mocking the assassination, and universities are suddenly drawing lines on speech they ignored when it was less politically inconvenient.

On the surface, this is another red-versus-blue media fight. Look deeper and it’s something more dangerous: the collapse of shared norms about how we talk about our political opponents when they are harmed—or killed. It’s the latest chapter in a long-running story about how American political culture, left and right, is inching closer to treating real human lives as collateral in an endless culture war.

The longer arc: From "all politics is local" to "all politics is existential"

To understand this moment, you have to go back at least two decades.

- Mid-2000s: Political talk radio, cable news, and early blogs fuel increasingly aggressive, personalized attacks. "War" becomes a standard metaphor—on Christmas, on women, on religion, on truth.

- 2010s: Social media supercharges this shift. Algorithms reward moral outrage and tribal signaling. Studies from Yale and others show that high-outrage posts spread much further than calm or nuanced ones.

- Late 2010s–2020s: The language escalates. Political opponents are not just wrong; they’re threats to democracy, to children, to the planet. The leap from "you’re dangerous" to "your death was inevitable" or "you brought this on yourself" gets shorter.

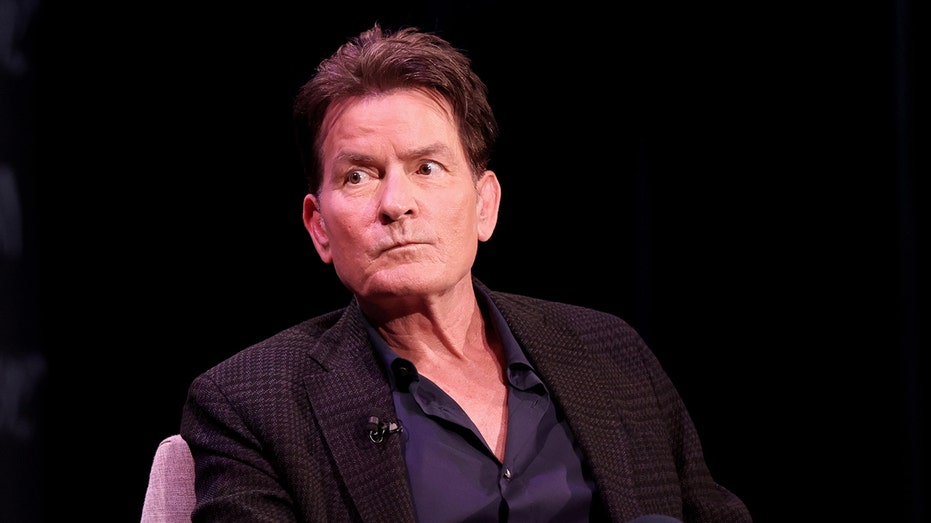

Charlie Kirk rose within this ecosystem as a highly visible conservative activist, especially on guns, race, gender, and LGBTQ+ issues. To many on the right, he represented unapologetic defense of the Second Amendment and traditional values. To many on the left—and particularly to LGBTQ+ people and people of color—he represented open hostility, dehumanizing rhetoric, and the normalization of bigotry.

In that context, Welch’s statement that "the person that justified his death was him" is not an isolated remark. It reflects a broader psychological and rhetorical pattern: when someone is perceived as having defended a policy that causes real harm or death to others, their own suffering is viewed as karmic, ironic, or self-inflicted. It’s the logic of cosmic payback, repackaged for the algorithmic attention economy.

What’s actually being argued here?

Underneath the insults and outrage, there are three overlapping debates:

- The moral boundary debate: Is there any line between criticizing a person’s politics and implying their violent death was deserved, inevitable, or self-justified?

- The consistency debate: Would people reacting to Kirk’s assassination apply the same standards if a progressive figure were killed by a right-wing extremist? Or vice versa?

- The grief as performance debate: In an era of media-savvy activism and ubiquitous cameras, when is public mourning authentic, and when is it "instrumentalized" for political or financial gain—and who gets to decide?

Welch’s comments sit squarely in the first two debates. By saying Kirk "justified" his own death through his defense of gun rights despite mass shootings, she’s making a brutal causal-moral argument: if you accept others dying as the price of your freedom, you implicitly accept your own death by that mechanism. It’s less a legal claim than a moral indictment.

Don Lemon’s position is more cautious but structurally similar. He rejects the idea that people he knows have "justified" the assassination and reaffirms that Kirk should be alive. But he underscores that Kirk "promoted guns" and accepted casualties as the cost of the Second Amendment—and that he died by gun violence. That’s a way of saying: his death was consistent with the world he advocated for, even if it wasn’t deserved.

What both positions risk, however, is collapsing the distinction between predictability and justification. It’s one thing to say, for example, that climate denial makes climate disasters more likely. It’s another to say a climate denier "justified" drowning in a flood. Welch’s phrasing—and some online reaction—slide toward the latter.

How social media incentives are distorting our response to political violence

There’s a structural reason these conversations sound increasingly cruel: the media and tech environment practically demands it.

- Outrage = reach: A 2019 study in Science Advances found that each additional moral-emotional word ("disgrace," "evil," "sick") in a tweet increased its retweet rate by roughly 20%. That’s the incentive structure Welch, Kirk’s critics, and his defenders are all operating in.

- Grief as content: Public mourning is now instantly scrutinized, clipped, and reframed. Erika Kirk’s town hall appearance and DealBook interview weren’t just spaces to process loss; they were content—fodder for supporters, enemies, and media outlets alike.

- Performance suspicion: Because everyone knows the camera is always on, sincerity itself becomes suspect. Lemon’s description of Erika Kirk’s grief as "acty" taps into this cultural suspicion: grief can’t just be grief; it must be a brand move.

The result is a vicious feedback loop. Public figures are expected to respond to violence in ways that are simultaneously emotionally raw and politically sharpened. Their critics then appraise that response not primarily as a human reaction to trauma but as a strategic performance that can be dissected, mocked, or monetized.

Welch’s accusation that Erika Kirk is a "grifter" weaponizing gender and Christianity is part of a broader trend of calling political opponents’ identities "props" while insisting one’s own identities are authentic and politically consequential. That move isn’t unique to the left or the right; it’s become standard in identity-inflected political discourse.

The asymmetry problem: What if the roles were reversed?

A useful stress test for any reaction to political violence is to ask: would the same reasoning be applied if the ideological roles were reversed?

Imagine a prominent progressive activist, outspoken on police abolition and anti-gun measures, is assassinated. A right-wing commentator then says: "The person who justified her death was her. She said increased social disorder and risks were necessary costs of dismantling oppressive systems." The internet would rightly explode with accusations of victim-blaming and moral depravity.

Welch’s language about Kirk isn’t identical to that hypothetical, but it rhymes with it. It implies that advocacy for a policy regime that produces violence makes one morally accountable for becoming a victim of that violence. If this standard takes hold, it becomes trivially easy to rationalize almost any politically motivated killing.

This isn’t just a moral hazard; it is strategically shortsighted. Once the norm becomes, "You accepted X risk as part of your politics, so you accepted your own death," every ideological camp can weaponize that logic against its opponents. The more polarized the environment, the more tempting that becomes.

Why marginalized anger is real—and why it still has limits

Lemon’s comments add a different layer: the reaction of communities that felt directly targeted by Kirk’s rhetoric. Many LGBTQ+ people and people of color heard years of Kirk’s commentary as not just disagreement, but dehumanization. For those groups, the assassination may have been experienced not as random tragedy but as violently poetic irony.

That reaction has a history. Marginalized communities have long used dark humor and schadenfreude as coping mechanisms in the face of oppression. You can find similar emotional dynamics around the death of segregationists in the 1960s or anti-gay crusaders in the 1990s. That doesn’t make the reaction morally clean, but it makes it intelligible.

The challenge is separating an understandable emotional response from a publicly endorsed moral standard. It’s one thing for a private citizen to confess, "I’m not sad he’s gone given what he stood for." It’s another for a prominent media voice to frame the victim’s death as something he morally "justified" through his policy positions. The first is messy human emotion. The second is a normalization of rhetorical blame for political murder.

Universities, free speech, and the sudden rediscovery of boundaries

The arrests, expulsions, and disciplinary actions against students mocking Kirk’s death highlight another fault line: institutions that have often tolerated—if not enabled—intense, sometimes dehumanizing political rhetoric are now scrambling to draw boundaries when the target is on the other side.

Universities that defended fiery campus speech as part of intellectual diversity are now disciplining students for "disturbing" comments at a vigil. Critics see a double standard: harsh rhetoric against conservatives gets a different institutional response than equally harsh rhetoric against progressives or marginalized groups.

Legally, most of this behavior falls under protected speech unless it directly incites violence or constitutes a true threat. But institutional policies aren’t just legal questions; they are normative ones. What kind of campus culture do we want when it comes to reacting to political violence? What’s the difference between legitimate critique of a dead person’s ideas and gleeful mockery of their killing?

We’re seeing institutions try to retroactively draw lines that should have been articulated long ago: you can condemn someone’s politics without celebrating their assassination. The fact that they’re doing it under intense political scrutiny only fuels accusations of partisanship and hypocrisy.

Looking ahead: The risk of assassination becoming another culture war "genre"

The most troubling possibility is that political assassinations—and their aftermaths—evolve into a recognizable content genre: instant blame, instant narrative, instant alignment with one’s existing worldview. Each killing becomes another opportunity to litigate which side’s rhetoric is more dangerous while quietly normalizing the idea that such violence is an expected, if regrettable, feature of our politics.

Several trends to watch:

- Escalation in rhetorical tit-for-tat: The more assassination and political violence are rationalized or framed as inevitable outcomes of "extremist" views, the more each side will feel justified in seeing its opponents not as fellow citizens but as legitimate targets of rage.

- Broad-brush blame: Polling that finds majorities in one party blaming "extremist rhetoric" for an assassination can easily morph into blaming the entire party or movement, cementing collective guilt narratives.

- Hardening of emotional camps: People who detest Kirk will point to his record to justify emotional detachment from his death. His supporters will use left-wing schadenfreude as proof that their opponents are irredeemable. Both sides walk away feeling more virtuous, and less capable of empathy.

- Policy paralysis: Ironically, the more each side weaponizes a killing to indict the other’s rhetoric, the harder it becomes to have sober conversations about actual risk factors, weapon access, and political radicalization.

The bottom line

This episode is not just about whether Jennifer Welch went too far or whether Erika Kirk’s grief is authentic. It’s about whether we’re willing to maintain even minimal moral norms around how we talk about political opponents when they are victims of violence.

We are entering a phase of politics where the temptation to see violent deaths as morally fitting—"you lived by that sword"—is growing. The deeper question isn’t whether that temptation is understandable. It’s whether we will let it shape our public discourse, our institutional responses, and ultimately our sense of which lives are still off-limits as targets in a permanent political war.

Because once enough people agree, even implicitly, that some political enemies "justified" their own assassination, the line between rhetoric and permission gets dangerously thin.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One of the most troubling undercurrents in this story is how quickly real human death is being converted into narrative ammunition. We see it in the way Welch frames Kirk’s assassination as something he effectively signed off on by defending gun rights, and in the way detractors attack his widow’s sincerity while she is still in the rawest phase of grief. There is an important conversation to be had about the role of inflammatory rhetoric—on guns, race, gender, and democracy—in creating climates where violence feels more plausible. But that conversation is not helped by language that treats a killing as karmically appropriate or strategically useful. What’s missing across much of the discourse is a basic commitment to a shared norm: no matter how intense our disagreements, we refuse to see assassination as a morally fitting outcome for anyone. That norm doesn’t preclude hard critique of a public figure’s record; it insists only that we keep a firewall between condemnation of ideas and moral rationalization of murder. If we can’t agree on even that, the ground under democratic politics is shakier than most people are willing to admit.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.