The ‘Sharia Free America Caucus’ and the New Politics of Civilizational Fear

Sarah Johnson

December 18, 2025

Brief

An in-depth analysis of Texas Republicans’ new ‘Sharia Free America Caucus,’ exploring its historical roots, constitutional implications, and how civilizational rhetoric reshapes U.S. immigration, security, and identity politics.

Texas Republicans’ ‘Sharia Free America Caucus’ Is About Much More Than Sharia

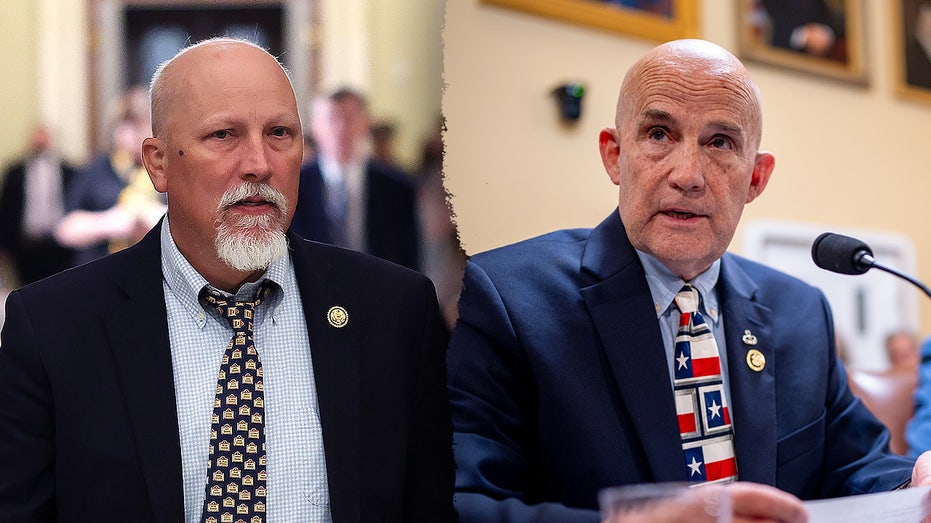

The launch of the “Sharia Free America Caucus” by Texas Republicans Keith Self and Chip Roy looks, on its face, like a niche effort targeting a fringe concern: the supposed spread of Islamic law in the United States. In reality, it’s a revealing moment in a much broader political project – one that fuses culture-war politics, anxieties over immigration and national identity, and a struggle over what counts as “Western civilization” in 21st‑century America.

To understand why this matters, we need to set aside the rhetoric about “sleeper cells” and ask three deeper questions: What concrete problem is this caucus claiming to solve? How does it fit into the long history of American fear politics around religious minorities and foreign ideologies? And what are the practical and constitutional stakes if its agenda moves from symbolism into actual law?

Beyond the Headlines: What This Caucus Really Signals

On the surface, the caucus seeks to do two key things:

- Advance legislation to bar foreign nationals who “adhere to Sharia” from entering the U.S.

- Push to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization.

These proposals are not new. They echo Trump-era initiatives and a longstanding drive by some conservative activists to frame political Islam as a unified, monolithic threat. But the timing and framing – a formal caucus to “protect Western civilization” – make this more than a policy debate about terrorism. It’s a signal that a segment of the Republican Party is doubling down on a civilizational narrative: a clash between vaguely defined “Western values” and an equally vague conception of “Sharia,” treated as inherently incompatible with American democracy.

That narrative has a long lineage – and a complicated relationship with both the Constitution and empirical reality.

Historical Echoes: From Anti-Catholic Panic to the ‘Sharia Threat’

American history is crowded with moments when a religious or ideological “other” was portrayed as fundamentally incompatible with the Constitution:

- 19th‑century anti-Catholicism: Catholic immigrants were accused of being loyal to the Pope rather than the U.S. and supposedly incapable of embracing democratic self-government.

- Anti-Mormon campaigns: In the late 1800s, federal power was used aggressively against Mormon polygamy, framed as a theocratic challenge to U.S. law.

- First Red Scare (1919–1920): Immigrant radicals were cast as carriers of a foreign ideology (Bolshevism) intent on overthrowing American institutions.

- McCarthyism: “Subversive” communists and sympathizers were depicted as infiltrating government, media, and academia – a language not far from today’s “sleeper cells” framing.

Each of these episodes combined real geopolitical concerns with exaggerated fears, often resulting in sweeping restrictions, loyalty tests, and civil liberties violations that later generations viewed as overreach.

The “Sharia threat” narrative follows this script. Since the early 2000s, and especially after 9/11, a network of activists and think tanks has promoted model legislation against “foreign law,” claimed there are secret plans to impose Sharia in U.S. courts, and argued that ordinary religious practices – from Islamic banking to family arbitration – are part of a broader Islamist project.

Empirically, the evidence for an impending “Sharia takeover” is thin. Where Islamic law appears in U.S. legal proceedings, it is generally treated the same way as Jewish halakha or Catholic canon law: as a voluntary moral or contractual framework that is always subordinate to constitutional and statutory law. When conflicts arise (for instance, where religious arbitration contradicts basic rights), U.S. courts have consistently enforced constitutional protections, not religious codes.

Sharia, Misunderstood: What It Is and What It Isn’t

The caucus intentionally blurs a critical distinction that most mainstream scholarship and security professionals make:

- Sharia as personal religious ethics: For most Muslims worldwide, “Sharia” refers to a broad set of moral and ethical principles guiding prayer, diet, family life, charity, and personal conduct.

- Sharia as state criminal code: In some non‑secular Islamic states (e.g., Iran, Saudi Arabia), aspects of religious law are codified and enforced by government, including corporal punishments, blasphemy laws, and gender-discriminatory rules.

By describing any “adherent to Sharia” as an existential threat, the caucus collapses ordinary religious practice into the most extreme manifestations of theocratic governance. That would be like treating any observant Catholic as a supporter of medieval inquisitorial practices – conceptually sloppy at best, and legally dangerous at worst.

Constitutionally, the line is clear: the First Amendment protects religious belief and practice; religious law has no formal governmental authority. U.S. courts may reference religious norms in the same way they might reference any foreign law or private contract, but only to the extent they are consistent with constitutional rights and public policy. That is why, as the original report notes, Sharia cannot be “carried out on any governmental level in the U.S.” – and why existing law already prevents its institutionalization.

What’s Really at Stake: Immigration, Identity, and Political Branding

If Sharia has no legal force in the U.S., why create a caucus to fight it?

The underlying battle is less legal than cultural and demographic. Chip Roy’s language about “Sharia adherents masquerading as ‘refugees’” and “sleeper cells” ties religious identity to national security risk and frames Muslim immigration as inherently suspect.

This aligns with several broader trends:

- Post‑9/11 securitization of Islam: The association between Muslim identity and terrorism, heavily amplified in media and politics, persists despite data showing that the overwhelming majority of Muslims in the U.S. are law-abiding and that terror plots are rare and often disrupted.

- European anxieties as cautionary tales: References to unrest in the U.K. and France invoke real integration and extremism challenges, but often in simplified form – ignoring differences in social policy, colonial history, and policing that make European dynamics an imperfect analogy to the U.S.

- Civilizational rhetoric in right‑wing politics: Positioning politics as a defense of “Western civilization” allows politicians to tie together disparate issues – immigration, education, LGBTQ+ rights, religious freedom – under a single, existential frame.

Within the Republican Party, such moves also have intra‑party value. Forming a caucus creates a brandable platform to showcase hardline stances, fundraise, and pressure leadership. Even if the caucus remains “largely symbolic,” symbols matter: they shape agendas, normalize certain frames, and send signals to activists and donors.

Constitutional and Policy Red Flags

The most tangible proposal associated with this caucus – banning foreign nationals who “adhere to Sharia” – raises immediate constitutional and practical concerns:

- Vagueness and enforceability: What does it mean to “adhere” to Sharia? Most observant Muslims would say they do. Would consular officers interrogate applicants’ theology? Rely on mosque attendance or religious dress? Such a standard would be almost impossible to apply consistently, and it would invite arbitrary, discriminatory decision-making.

- Religious test in immigration policy: While the Constitution’s protections are strongest for those on U.S. soil, U.S. law and international obligations still constrain overtly discriminatory immigration rules. Policies that target an entire religion’s adherents have already faced heavy scrutiny in litigation over the Trump administration’s travel bans.

- Chilling effect on domestic religious freedom: Even if the ban functionally operates abroad, its premise – that adherence to a faith’s legal-ethical tradition is incompatible with American life – can bleed into domestic politics, justifying surveillance, workplace discrimination, or community harassment.

The effort to label the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization raises different questions. The Brotherhood is a sprawling, decentralized movement with variants ranging from political parties in some countries to violent offshoots in others. U.S. security agencies have historically been cautious about an across-the-board terrorist designation precisely because it could blur distinctions between armed groups and nonviolent political actors, and entangle U.S. diplomacy in complex regional politics.

Expert Perspectives: Security vs. Symbolism

Security and legal experts have long warned that overbroad, ideologically driven measures can undermine real counterterrorism work.

Dr. Lorenzo Vidino, director of a program on extremism at George Washington University, has argued in his research that while certain Islamist networks do seek influence in Western societies, “lumping all pious Muslims or even all Islamists into a single extremist category is counterproductive. It alienates potential partners and fuels narratives of persecution that jihadist groups exploit.”

On the legal side, Prof. Asma Uddin, a religious liberty scholar, has noted that “the Constitution already provides a powerful firewall against religious law being imposed on unwilling parties. Where conflicts arise, courts have consistently upheld constitutional rights over religious norms. The ‘Sharia threat’ narrative misrepresents both American law and Muslim practice.”

Former DHS officials have made a similar point: resources are finite. Every dollar and hour spent chasing a diffuse ideological “threat” defined primarily by religious identity is a dollar and hour not spent targeting concrete plots, radicalization pipelines, or online extremist networks where violence is actually incubated.

Data and Reality Check

Available data complicates the caucus’s alarmist framing:

- Muslim population in the U.S.: Pew Research Center estimates roughly 3.5 million Muslims in the U.S., about 1% of the population. They are among the most diverse religious groups by race and ethnicity.

- Integration indicators: Surveys show that a large majority of American Muslims express pride in being American and support pluralism and democratic norms at rates similar to or higher than other religious communities.

- Terrorism trends: Since 9/11, U.S. terrorism fatalities have included attacks by jihadist-inspired individuals but also a significant number linked to far-right and white supremacist extremism. Federal data and academic research emphasize a multipolar threat landscape rather than a singular Islamic threat.

- “Sharia in courts”: Studies of state “anti‑Sharia” laws (adopted or proposed in dozens of states) show very few actual cases where Islamic law posed a genuine conflict with U.S. law – and those were resolved under existing constitutional principles.

This doesn’t mean there are no security risks associated with jihadist ideologies. It does mean that a religiously defined ban or a sweeping “Sharia caucus” is a blunt instrument for a nuanced challenge – one more likely to generate political capital than measurable security gains.

Looking Ahead: Potential Consequences and Fault Lines

Whether this caucus remains a symbolic messaging vehicle or evolves into a legislative force will depend on several factors:

- Election cycles: In periods when immigration and security fears spike – after an attack, during border crises, or in heated campaigns – such initiatives can move from the fringe to the mainstream as politicians look for simple, muscular responses.

- Judicial pushback: If the caucus’s legislative proposals advance, courts are likely to become the key arena. Legal challenges over religious discrimination, due process, and vagueness could mirror past battles over travel bans and loyalty tests.

- Party dynamics: The caucus could deepen divides within the GOP between those emphasizing big-tent outreach (including to socially conservative Muslim voters) and those prioritizing civilizational rhetoric and restrictionist immigration policies.

- Community relations: On the ground, the rhetoric itself matters. Past spikes in anti-Sharia campaigns have correlated with increases in anti-Muslim bias incidents and hate crimes. Community leaders and law enforcement may have to manage heightened tensions, regardless of whether the caucus’s bills ever pass.

There is also a strategic question for those genuinely concerned about extremism: does casting millions of Muslims – abroad and at home – as potential Sharia-driven saboteurs help or hinder efforts to combat radicalization? Most counterterrorism professionals would say it hinders: effective prevention relies on cooperation, trust, and precise targeting, not blanket suspicion.

The Bottom Line

The “Sharia Free America Caucus” is less about a realistic threat of Islamic law displacing the U.S. Constitution and more about codifying a worldview in which “Western civilization” is under siege from a religiously defined other. It taps into a long American tradition of panic over allegedly incompatible ideologies – from Catholicism to communism – and repeats many of the same mistakes: conflating belief with subversion, using law as a cultural weapon, and underestimating the capacity of American institutions to manage diversity.

Underneath the dramatic branding is a familiar trade‑off: symbolic political gains for those championing the caucus versus potential costs to constitutional norms, minority rights, and the effectiveness of real security work. As with past moral panics, the risk is that by fighting an exaggerated enemy, policymakers end up injuring the very principles – rule of law, religious freedom, equal citizenship – they claim to defend.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One underexplored dimension of this story is how such a caucus interacts with America’s own self‑image as a champion of religious freedom. Historically, the U.S. has used its constitutional protections as a soft-power asset, contrasting itself with regimes that persecute minorities or enforce religious codes through the state. A high-profile congressional caucus defined by opposition to a particular religion’s legal-ethical tradition complicates that narrative. Even if framed as a security measure, the rhetoric easily reads abroad as hostility to Islam itself, not merely to violent extremism. That perception carries foreign policy costs: it can weaken U.S. credibility when criticizing other countries’ religious repression and make cooperation with Muslim-majority allies more fraught. Domestically, it also raises a dangerous precedent: once the idea of excluding people based on religious adherence is normalized in immigration, it becomes easier to justify new forms of ideological or religious screening in other areas. The question lawmakers rarely confront is whether the short-term political gains from such symbolism are worth the long-term erosion of the universal principles they say distinguish American ‘Western civilization’ from the very theocracies they oppose.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.