Venezuela’s Tanker Blockade: How the World’s Biggest Oil Reserves Became a Geopolitical Choke Point

Sarah Johnson

December 18, 2025

Brief

Trump’s tanker blockade against Venezuela tests a new model of energy coercion, targeting the global shadow fleet and weaponizing the world’s largest oil reserves with far-reaching geopolitical implications.

Venezuela’s Oil Blockade: A High-Stakes Experiment in Weaponizing the World’s Largest Reserves

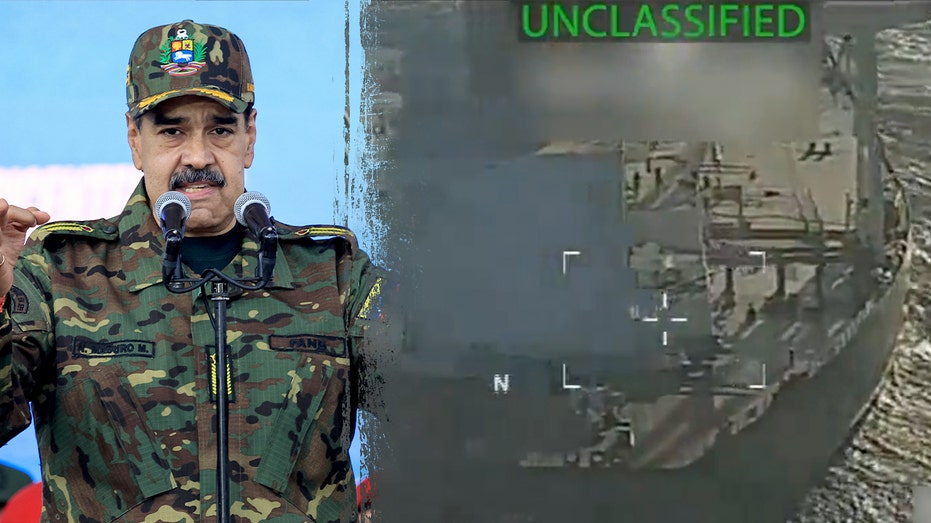

Donald Trump’s decision to declare Venezuela’s government a foreign terrorist organization and order a “total and complete blockade” on sanctioned oil tankers is not just another sanctions headline. It is a test case for how far a major power can go in criminalizing an energy-exporting state, targeting the logistics of a global black market in oil, and reshaping the geopolitics of crude in the process.

At the center of this story is a stark paradox: the holder of the world’s largest proven oil reserves is being choked at the point where its oil physically touches global markets. This isn’t just about Caracas and Washington; it’s about how the energy system functions when a G‑20 country tries to police a “shadow fleet” of roughly 1,000 tankers that keep sanctioned oil — Iranian, Russian, Venezuelan — flowing despite Western pressure.

Why This Blockade Matters Now

Venezuela’s estimated 300+ billion barrels of crude — about 20% of the world’s total — should make it an oil superpower. Instead, it has become a case study in how reserves no longer equal power when governance fails, infrastructure collapses, and financial access is shut off.

The tanker blockade attempts something new: rather than just sanctioning state-run oil companies or buyers, it targets the floating infrastructure of sanctions evasion itself — those “ghost ships” that change names, flags, and ownership and switch off transponders to move illicit crude. If even partially effective, this approach could become the template for future energy coercion against other states, from Russia to Iran.

How Venezuela Got Here: From Oil Power to Petro-Dependency Trap

To understand the stakes, you need the longer arc of Venezuela’s oil story:

- 1950s–1980s: Oil-funded modernity. High oil prices and strong production turned Venezuela into one of Latin America’s wealthiest societies. Its state oil company, PDVSA, was once considered among the best-run in the world. Oil built highways, universities, and a middle class.

- 1990s: Early signs of the resource curse. Overdependence on oil revenues made other sectors uncompetitive. Manufacturing and agriculture withered, classic symptoms of what economists call “Dutch Disease.”

- Chávez era (1999–2013): Political control over PDVSA. Hugo Chávez purged PDVSA’s technocratic leadership after a 2002–03 strike, transformed it into a political arm of the state, and diverted oil income into social programs and patronage rather than reinvestment. Production began its long decline.

- Maduro era (2013–today): Collapse meets sanctions. Nicolás Maduro inherited a hollowed-out company, crumbling infrastructure, and falling oil prices. U.S. sanctions from 2017 onward, especially on PDVSA and dollar financing, accelerated the collapse. By 2020, output had crashed from roughly 3.2 million barrels per day at its peak to under 800,000 — a decline of more than 70%.

Venezuela’s crisis is the extreme version of a broader pattern seen in Iraq in the 1990s, Libya after 2011, and Iran under sanctions: when political instability, corruption, and sanctions combine, even enormous reserves can’t translate into sustainable production or revenue.

The Shadow Fleet: How “Ghost Ships” Keep Sanctioned Oil Alive

What the blockade directly targets is not PDVSA as an entity but the logistics system that has evolved to keep its oil (and others’) flowing despite sanctions. That system is built on three pillars:

- Maritime opacity. Tankers change flags (often to states with weak oversight), alter names, and are owned via layered shell companies in opaque jurisdictions. This makes it difficult to identify ultimate beneficial owners or enforce sanctions effectively.

- Dark operations. Ships disable Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponders, go “dark” in contested waters, and conduct ship-to-ship transfers at sea. Oil loaded in Venezuela can end up on a vessel that later appears, on paper, to have originated elsewhere.

- Hybrid insurance and financing. While Western insurers and banks have pulled back from sanctioned cargoes, alternative networks — often linked to Russia, China, or smaller regional players — provide financing, insurance-like guarantees, and trade credit for illicit flows.

The U.S. interception of one “nondescript” tanker in December, while symbolic, is mainly proof-of-concept. It signals that Washington is willing to extend its counter-terrorism and counter-proliferation playbook — built over decades to chase weapons and terror financing — into the domain of energy logistics.

From Sanctions to Criminalization: A Legal and Strategic Escalation

Labeling the Venezuelan regime a foreign terrorist organization is more than rhetorical. It opens a broader toolkit of U.S. authorities designed for non-state terror groups but now applied to a sitting government:

- Expanded extraterritorial reach. U.S. prosecutors can bring more aggressive cases against foreign shipowners, insurers, traders, and financiers who touch the U.S. system even tangentially.

- Asset seizures as a strategy. The tanker seizure is likely an opening salvo. Ships, receivables, and even refiner payments could be targeted as “terror-linked” assets, raising risks for any actor dealing in Venezuelan oil.

- Military signaling. Deploying thousands of troops and an aircraft carrier to the region is less about literal blockade enforcement at every point and more about credibility: it signals that interdiction is not just a paperwork exercise but backed by force if necessary.

This blurs a long-standing line: sanctions used to be primarily economic tools. Framing a regime as a terrorist entity moves the conflict into quasi-military and criminal space, with implications for how other countries — including allies — respond.

Who Really Gets Hurt? The Regime vs. the Population

Supporters of the blockade argue that because Venezuela is “wholly dependent” on oil, choking off illicit tanker routes will weaken Maduro’s power base and hasten political change. History offers a more complicated picture:

- Iraq in the 1990s: Comprehensive sanctions gutted civilians’ living standards and health outcomes but did not dislodge Saddam Hussein.

- Iran since 2012: Sanctions sharply constrained revenue and investment, but the Islamic Republic adapted through regional gray networks and political repression.

- Cuba after 1962: Decades of embargo did not produce regime change, but did shape political discourse and alignments in the region.

Venezuela already faces hyperinflation, mass emigration (more than 7 million Venezuelans have left in the past decade), and severe shortages. A tighter chokehold on oil revenues risks deepening the humanitarian crisis unless paired with robust, depoliticized humanitarian channels, which so far remain limited and contested.

Ironically, the regime’s reliance on a narrow circle of loyalists and security forces can make it more resilient under pressure: reduced state revenues often hit ordinary citizens first, while insiders prioritize their own pay and benefits. The blockade may therefore harden authoritarian dynamics in the short term, even if it weakens the state’s long-run economic foundations.

The Global Oil System: Why One Country’s Blockade Has Systemic Ripples

On its own, Venezuela’s current export volumes are no longer large enough to shock global prices in the way a full-scale disruption of Gulf oil might. But the blockade interacts with several broader trends:

- Fragmentation of oil markets. Sanctions against Iran, Russia, and Venezuela have already created a multi-tiered system: a “clean” market dominated by OECD buyers and a discounted, opaque market serving states and firms willing to bear political and legal risk.

- Rise of the discount barrel. China, India, and others have opportunistically bought heavily discounted oil from sanctioned states. Cutting off Venezuela’s shadow fleet would alter these flows and potentially raise costs for refiners that rely on heavy, sour crude similar to Venezuelan grades.

- Strategic diversification. Major importers have been trying to diversify supply away from politically risky producers. A prolonged blockade could accelerate long-term investments in non-OPEC supply, renewables, and efficiency — but those shifts play out over years, not months.

In the near term, the bigger risk isn’t a sudden supply shock but heightened volatility and a deeper normalization of “illegal” or quasi-legal oil trade, as actors innovate around enforcement.

What’s Being Overlooked: China, Russia, and the Limits of U.S. Leverage

Most coverage frames this as a bilateral U.S.–Venezuela showdown. That leaves out two crucial players: China and Russia.

- China as creditor and buyer. Chinese lenders have extended tens of billions of dollars in oil-backed loans to Venezuela over the past 15 years. Even as Beijing has reduced exposure, it retains strong incentives to see Venezuelan production recover in some form. Chinese firms and intermediaries are key nodes in the shadow fleet and associated financing systems.

- Russia as logistics partner. Russian entities have helped manage Venezuelan crude flows, both as traders and as providers of logistical and technical expertise. As Russia faces its own oil sanctions, Moscow and Caracas have converging interests in building alternative networks.

The blockade will test whether U.S. military and financial power can meaningfully constrain state-backed participants in the gray oil trade. If large Chinese or Russian-linked tankers are interdicted or sanctioned more aggressively, we move closer to a world where energy logistics become a theater of great-power rivalry, not just a tool against weaker states.

Could This Strategy Backfire?

There are several plausible unintended consequences worth watching:

- Risk migration. Smaller, older, less-regulated vessels may take on a greater share of the illicit trade as reputable or mid-tier players pull back. That raises environmental risks — from spills to accidents — particularly in congested or ecologically fragile waters.

- Norm erosion at sea. As the U.S. and others assert more aggressive rights to interdict tankers in international waters, rival powers may feel justified in mirroring these tactics for their own ends, undermining long-standing maritime norms.

- Entrenchment of Maduro. If the regime successfully frames the blockade as imperial aggression, it can use nationalist rhetoric to justify further repression and delay any internal splits within the ruling coalition.

None of this means the strategy is doomed. But past precedents suggest that sanctions and blockades are more effective when paired with credible political off-ramps, clear benchmarks for relief, and robust multilateral backing. Those elements are, at best, still in formation here.

What to Watch Next

Several indicators will show whether this blockade is changing the game or merely raising costs at the margins:

- Venezuelan export volumes and discounts. A sustained drop in exports or a deepening discount relative to benchmarks like Brent would indicate real pressure on the regime’s cash flow.

- Behavior of major refiners. If buyers in Asia or elsewhere cut back on Venezuelan crude or demand steeper discounts to compensate for legal risk, that amplifies the blockade’s effect.

- Patterns in AIS “dark activity.” A shift in where and how frequently tankers go dark could show adaptation — or deterrence — in the shadow fleet.

- Regional political alignment. Responses from Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Caribbean states will shape whether the blockade becomes a hemispheric initiative or a unilateral U.S. effort that others quietly work around.

The Bottom Line

Venezuela’s oil reserves are vast, but reserves without governance, investment, and market access are closer to a curse than a blessing. The U.S. tanker blockade is an ambitious attempt to weaponize that contradiction, turning the country’s dependence on oil exports into a lever for political change.

The broader story, though, is about the future of energy geopolitics. As more states lean on sanctions and extraterritorial enforcement, the global oil system risks bifurcating into an increasingly transparent, rule-bound market and a murkier, politically contested shadow system. Venezuela is where that contest is currently most visible — but it will not be the last battleground.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One under-discussed dimension of this blockade is its long-term impact on international norms governing the use of economic coercion. By fusing terrorism designations, financial sanctions, and quasi-blockade tactics against a sovereign state, Washington is setting precedents that other powers can invoke later, possibly in contexts far removed from Venezuela. What happens if China applies a similar logic to a neighbor over disputed territory, or if Russia justifies interdictions in the Arctic by claiming security threats? The immediate focus on Maduro’s regime obscures this broader normative drift. There is also a strategic question: does repeatedly turning to maximum-pressure tools — sanctions, blockades, terror labels — reduce their marginal effectiveness over time, as targeted states learn to network and hedge against them? Venezuela, with its already devastated economy, may not be the place where these questions become acute, but it is where the contours of a more fragmented, coercion-heavy international economic order are being sketched in real time.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.