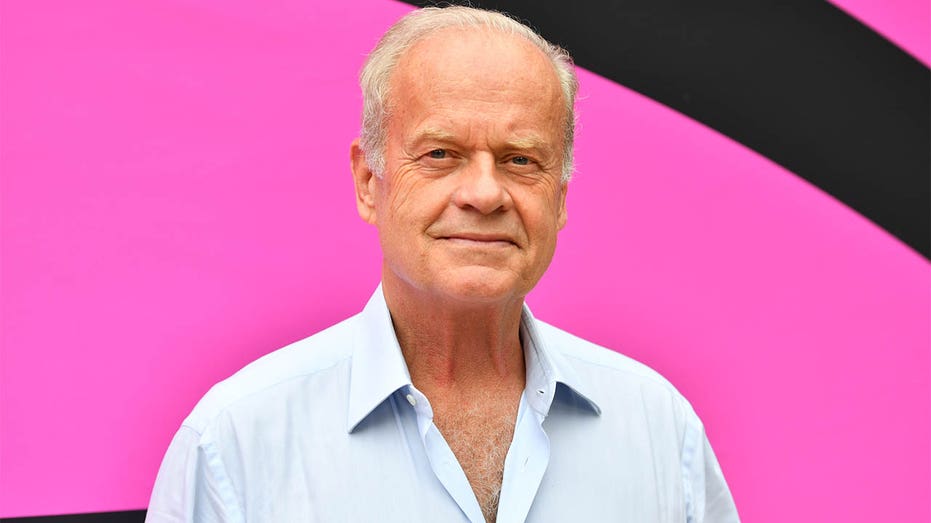

Kelsey Grammer’s Los Angeles Problem: What His ‘Nincompoops’ Comment Reveals About a City in Crisis

Sarah Johnson

December 16, 2025

Brief

Kelsey Grammer’s jab at Los Angeles leadership isn’t just a celebrity gripe. It crystallizes deeper anxieties about governance, wildfires, and Hollywood’s shifting relationship with a city in identity crisis.

Kelsey Grammer vs. Los Angeles: What One Actor’s Frustration Reveals About a City in Identity Crisis

When Kelsey Grammer dismisses Los Angeles leadership as “nincompoops” and admits he knew the city wasn’t for him “the minute I got here,” it’s easy to treat it as just another celebrity rant. But behind the quip is something more consequential: a symbol of how even Hollywood’s insiders are becoming powerful narrators of LA’s perceived decline, reshaping the story the city tells about itself.

Grammer’s comments sit at the intersection of three bigger shifts: the politicization of Hollywood voices, the growing narrative of an exodus from California, and the public’s collapsing trust in local governance amid wildfires, housing crises, and visible disorder. His frustration is less about traffic or vibe and more about what happens when a place that sells dreams looks increasingly like it’s struggling to manage basic realities.

LA, Hollywood, and the Long History of Love-Hate

Actors feuding with Los Angeles is almost as old as the film industry itself. From the 1970s onward, LA has repeatedly played a double role in American culture: both as a promised land for reinvention and as a cautionary tale of sprawl, smog, and inequality.

In the 1980s—when Grammer moved west for his breakthrough role as Frasier Crane on “Cheers”—LA was still riding the high of its entertainment boom but already grappling with crime, racial tensions, and suburban sprawl. The 1992 LA riots, the Northridge earthquake, and waves of deindustrialization all chipped away at the myth of an endlessly optimistic city. Every decade since has produced its own version of the LA “doom loop” narrative.

What’s different now is how closely that narrative ties to governance. Wildfires, homelessness, affordability, and policing aren’t just seen as tragic or complex—they’re increasingly framed as the result of political incompetence or ideological overreach. Grammer’s “nincompoops” comment is a blunt version of a criticism you can hear in LA coffee shops, real estate offices, and studio lots, often couched in softer language but carrying the same message: powerful people aren’t managing the basics.

From Wildfires to ‘Malfeasance’: The Governance Question

Grammer doesn’t just say LA is “challenging.” He explicitly suggests “malfeasance in office” in connection with fire prevention and broader mismanagement. That’s a serious charge, and it reflects how environmental disasters have become political litmus tests in California.

California has experienced a dramatic escalation in wildfire activity over the past decade. According to state data, 9 of the 20 largest wildfires in California history have occurred since 2017. While climate change and drought are core drivers, the debate over “mismanagement” centers on:

- Forest and brush management: How aggressively to clear undergrowth, use controlled burns, and harden infrastructure.

- Land-use decisions: Building high-value homes in high-risk wildland-urban interface zones like Pacific Palisades and hillside communities.

- Utility oversight: Aging power infrastructure has been linked to some of the state’s most devastating fires.

When someone like Grammer says “somebody took their eye off the ball,” he’s channeling a widespread perception that state and local officials have been slow to translate decades of fire science into consistent policy and investment—especially in affluent, politically connected areas that assumed they were protected.

Here’s what’s often overlooked: the same governance structures being blamed for wildfire failures are also the ones tasked with solving homelessness, transportation, and housing costs. So each crisis reinforces a broader story of systemic dysfunction. For a public already skeptical of institutions, every fire, encampment, or high-profile crime incident becomes further proof that “nincompoops are running things.”

Hollywood’s Political Realignment, One Actor at a Time

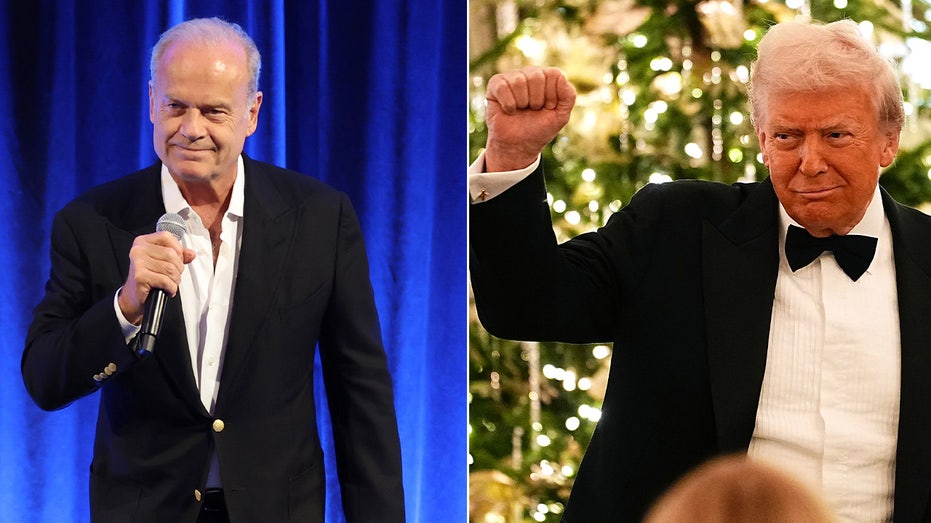

Grammer has long identified as conservative, and he recently called Donald Trump “one of the greatest presidents we’ve ever had.” That positions him as a minority voice in an industry often perceived as uniformly liberal. His comments about LA therefore land in an already polarized media environment, where celebrity opinions are treated as political content rather than just personal anecdotes.

But the more interesting trend isn’t that Grammer is conservative—it’s that Hollywood’s internal ideological map is fragmenting, and those fractures are now public:

- Openly conservative actors like Grammer, Clint Eastwood, and others provide a counter-narrative to the idea of a monolithic liberal Hollywood.

- Centrist and apolitical creatives increasingly complain privately about crime, taxes, and regulation, even if they don’t embrace right-wing politics.

- Progressive voices inside LA continue to push for criminal justice reform, stronger tenant protections, and climate action, often clashing with more business-oriented factions.

Grammer’s critique lands at the overlap of all three. He’s not just attacking “LA” as a lifestyle; he’s challenging a political model that many associate with California’s progressive governance. For conservatives nationally, quotes like “we’ve got nincompoops running things” become cultural evidence that even Hollywood insiders agree liberal cities are failing.

Celebrities Fleeing LA: Narrative or Trend?

Grammer says he’s “hoping that we find our corner in Los Angeles,” not threatening to leave. But his comments come amid a steady drumbeat of stories about actors, musicians, and executives moving to Texas, Florida, Tennessee, or back East.

So far, the data is nuanced:

- California has seen net domestic outmigration for several years, with hundreds of thousands more residents leaving than arriving.

- However, the state still has over 39 million people, and LA remains one of the world’s dominant entertainment hubs.

- Many high-net-worth individuals retain homes in LA while establishing residency elsewhere for tax and lifestyle reasons.

Yet perception can matter as much as numbers. When recognizable faces like Grammer or Danica McKellar publicly question LA’s appeal, they help normalize the idea that leaving—or at least detaching emotionally from the city—is rational. That has downstream effects on:

- Investment decisions by studios and streamers weighing where to expand production.

- Voter attitudes toward tax increases or large-scale public spending proposals.

- How younger creatives think about where they need to live to build a career.

If LA becomes seen not as the inevitable home of entertainment, but as one option among many—from Atlanta to Austin to Vancouver—then public criticism from its own stars carries more weight than it would have in the 1980s or 90s.

The Personal and the Political: Grammer’s Loss, Fires, and Resilience

One detail that could easily be missed in the soundbite is Grammer’s reflection on loss. He mentions having “a house full of refugees” from recent fires and notes, “When you lose everything you have, and that’s happened to me a couple of times in my lifetime…”

Grammer has endured multiple personal tragedies—family murders, accidents, and addiction struggles—that have shaped his worldview. That context matters: when he talks about picking yourself up “one foot in front of the other,” he’s speaking from experience in both personal and physical devastation.

This is where his critique of LA takes on a deeper layer. He’s essentially asking: after disaster, does the system help you rebuild, or are you mostly on your own with support from neighbors and private networks? His emphasis on a “house full of refugees” and “a lot of people around who want to support” frames community solidarity as a counterweight to institutional failure.

In that sense, his politics—more conservative, skeptical of government competence—line up with his lived experience. He’s not arguing that people will be abandoned; he’s arguing they’ll be saved by each other, not by the people “running things.”

What Grammer’s ‘Little Garden’ Says About the Future of LA

Perhaps the most revealing line is his hope to “find our corner in Los Angeles so we can keep our little garden, you know, growing and pristine.” That’s not just a metaphor for domestic happiness; it’s a concise description of how many Angelenos, wealthy and not, now think about the city.

Instead of believing in LA as a coherent, well-managed whole, people increasingly focus on creating safe, functional micro-environments—gated neighborhoods, curated social circles, private schools, private security, and hyper-local community efforts. The city becomes a patchwork of protected “gardens” separated by areas perceived as unsafe, ungoverned, or neglected.

The long-term risk is a feedback loop:

- Those with resources retreat into private solutions.

- Public systems become more strained and politically contested.

- Visible disorder or crisis feeds perceptions of broader decline.

- More residents disengage from shared institutions, further weakening them.

Grammer’s ambivalence—“I’m not crazy about it. But I also love it”—may be the most accurate emotional summary of how many LA residents currently feel. They’re attached to their “little gardens” but skeptical of the larger ecosystem that’s supposed to sustain them.

Expert Perspectives on LA’s ‘Nincompoop’ Problem

Urban governance experts caution against reducing complex systemic problems to incompetent individuals. Yet they acknowledge a real crisis of confidence in local leadership across many US cities, especially on issues like homelessness, public safety, and infrastructure.

Political scientist Dr. Raphael Sonenshein, who has written extensively about LA governance, has argued that the city’s fragmented power structures—multiple overlapping agencies, county/city divides, and a weak mayor system—can make accountability hard to pinpoint. In such an environment, any failure looks like generalized “nincompoopery,” even when the causes are structural.

Urban resilience researchers also point out that cities under climate stress face a compressed timeline: what once unfolded over decades is now happening in years. That makes visible failures more likely, and public patience shorter. When actors like Grammer publicly frame these failures as political malfeasance, they’re giving voice to a grievance that many feel but don’t always articulate.

What to Watch Next

The significance of Grammer’s comments isn’t about whether one 70-year-old actor stays in Los Angeles. It’s about whether LA can reverse a powerful story that’s taking hold among its own elites: that the city is mismanaged, precarious, and no longer the obvious center of gravity for creative life.

Key indicators to watch over the next few years include:

- Policy response to fires and climate risk: Does California scale up prescribed burns, grid hardening, and rebuilding restrictions in high-risk zones in ways that restore public confidence?

- Net migration patterns of high-income households: Do more entertainment professionals formally relocate their base of operations, or continue a “bi-coastal/multi-state” model while keeping a foothold in LA?

- Hollywood production geography: As incentives shift, do more major projects decamp permanently to other cities, or does LA retain its central role even if some talent moves away?

- Public trust levels: Surveys of residents’ confidence in city and county leadership on housing, safety, and climate resilience will show whether “nincompoops” remains a throwaway line or hardens into conventional wisdom.

If LA can demonstrate visible, measurable progress on its most pressing crises, the celebrity narrative may soften. If not, voices like Grammer’s will continue to shape not just how LA is perceived, but where the next generation of creators decides to put down roots.

The bottom line: Kelsey Grammer’s critique is less about one man’s annoyance with a difficult city and more about a broader cultural turning point. Los Angeles—once the embodiment of American possibility—is being reimagined by its own storytellers as a place where you fight to keep your “little garden” alive while wondering if the people in charge know what they’re doing. That perception, if left unaddressed, may prove more damaging to LA’s future than any single wildfire or policy failure.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One of the underexplored angles in the Grammer-Los Angeles story is how much of the governance critique is actually about class and geography. Wildfire losses in affluent enclaves like Pacific Palisades cut differently in the public imagination than chronic crises in poorer neighborhoods. When high-profile residents suddenly experience the kind of insecurity that lower-income Angelenos have been living with for years—whether it’s housing precarity, exposure to environmental risk, or unreliable public services—their outrage tends to be amplified and quickly translated into media narratives. But the structural problems they are now noticing didn’t start at the hillsides; they’ve been visible along the LA River, in the San Fernando Valley, and on Skid Row for decades. The question for policymakers is whether elite frustration will finally catalyze structural reforms that benefit the entire city, or simply accelerate the flight of those with resources into private solutions and other jurisdictions, further hollowing out the public sphere they’re criticizing.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.