Nick Reiner, a Dormant Death Penalty, and the Justice System’s Blind Spot

Sarah Johnson

December 18, 2025

Brief

Beyond the headlines, the Nick Reiner case exposes the contradictions of California’s symbolic death penalty, the limits of victims’ rights, and systemic failures around mental illness and prevention.

Nick Reiner, the Death Penalty, and the Limits of Family Voice: What This Case Really Exposes

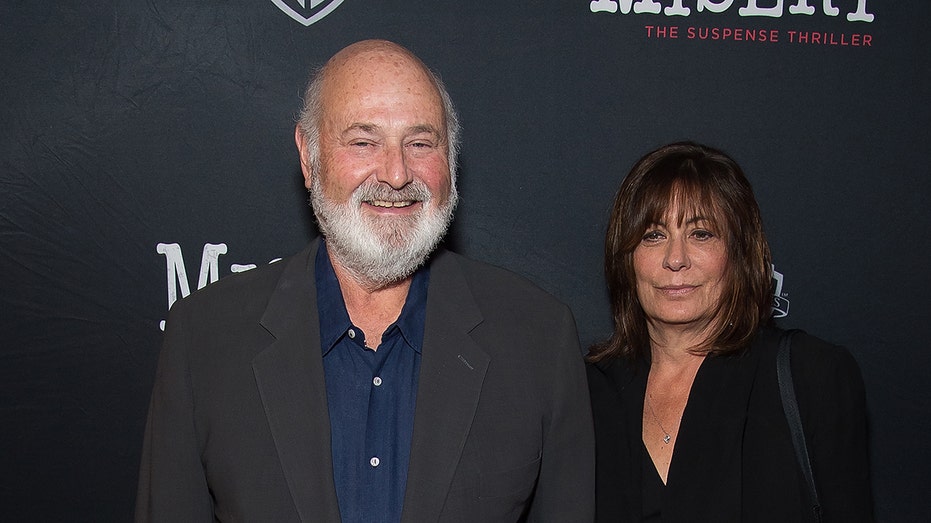

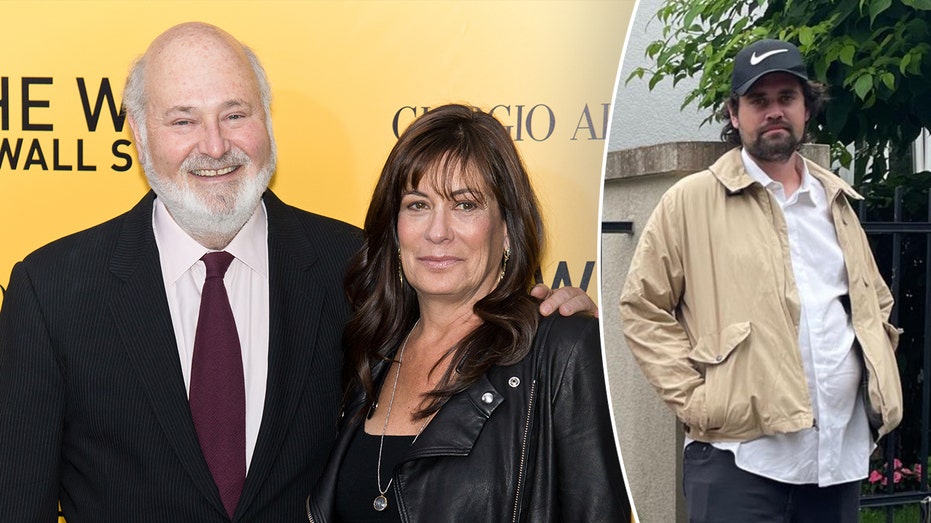

The killing of Rob and Michele Reiner, allegedly at the hands of their son Nick, is being framed as a celebrity tragedy and a potential death-penalty case. But beneath the headlines is a collision of three powerful – and often contradictory – forces in American justice: the politics of capital punishment, the growing role of victims’ rights, and the persistent failure to meaningfully address mental illness and addiction before they turn catastrophic.

What unfolds in Los Angeles over the coming months will not just determine Nick Reiner’s fate. It will highlight how much of our legal system is still built to respond after a disaster, rather than to prevent one – even when warning signs were visible for years.

The bigger picture: A death penalty that exists on paper but not in practice

Nick Reiner is charged with two counts of first-degree murder with special circumstances for multiple murders and alleged use of a deadly weapon. On paper, that exposes him to either life without parole or the death penalty. In reality, the legal landscape in California is far murkier.

California has not executed anyone since 2006. In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom imposed a moratorium on executions, shut down San Quentin’s execution chamber, and halted lethal injection protocols. The death penalty remains in the state constitution and penal code, but it is essentially a symbolic sentence – severe in name, unenforceable in practice unless a future governor or voters change course.

This isn’t a California-only phenomenon. Across the U.S., capital punishment has entered what many legal scholars call a “twilight era”:

- Executions have fallen from 98 in 1999 to fewer than 30 in recent years.

- Twenty-something states have abolished the death penalty outright; several others, like California and Oregon, maintain it but do not use it.

- Juries and prosecutors are increasingly reluctant to pursue death sentences, particularly in cases involving mental illness or serious addiction histories.

In that context, the Reiner case is likely to become a flashpoint in an emerging debate: if the death penalty is functionally off the table, why are prosecutors still seeking it, and what does it mean to sentence someone to a punishment the state has effectively vowed not to carry out?

Victims’ rights vs. prosecutorial discretion: How much does the family’s voice really matter?

Los Angeles County District Attorney Nathan Hochman has emphasized that the “thoughts and desires of the family” will be considered in any decision to seek the death penalty. That nod to the Reiner family isn’t just political; it reflects a deliberate shift in American criminal justice over the past four decades.

California’s Marsy’s Law – a high-profile victims’ rights amendment passed in 2008 – guarantees families the right to confer with prosecutors, make impact statements, and be heard at key stages of the process. But as criminal defense attorney Jo-Anna Nieves points out, that voice is “meaningful but not controlling.” Courts have long warned that sentencing, especially in capital cases, cannot be delegated to victims or their families.

This tension is crucial in a case like this, where the “victim’s family” and the accused are the same family. Some relatives may want the maximum possible punishment. Others may see their brother as both alleged perpetrator and another victim – of mental illness, addiction, or a system that didn’t intervene in time.

Historically, families in parricide cases (where children kill parents) often oppose the harshest sentences. They may seek treatment, long-term confinement, or acknowledgment of psychiatric issues rather than death or absolute incapacitation. If some Reiner relatives argue against capital punishment, Hochman will have to balance those requests against public pressure to be tough in a high-profile double homicide involving a beloved Hollywood figure.

What this really means: A system still unable to reconcile mental illness, violence, and punishment

Clues in the reporting hint at an all-too-familiar trajectory: a child described as “hyperactive” and “intense,” a long battle with addiction and volatility, periods where things looked “on the upswing,” and sudden, disturbing behavior leading up to the alleged murders. Witnesses from Conan O’Brien’s Christmas party describe Nick as “acting crazy” and “freaking everyone out.”

None of this is a diagnosis, and it would be irresponsible to speculate about a specific condition. But the pattern fits an increasingly common profile in serious violent crime:

- Early behavioral challenges recognized but not comprehensively treated in a coordinated way.

- Self-medication, substance use, or addiction layered on top of underlying mental health vulnerabilities.

- Intermittent periods of apparent stability misread as resolution rather than remission.

- An acute crisis – often involving family conflict – that becomes the flashpoint for tragedy.

California has spent years trying to build alternative responses: mental health courts, involuntary treatment mechanisms, and diversion programs. But those tools are often deployed only after repeated arrests or highly visible crises. For families like the Reiners – affluent, connected, able to cobble together yoga, private support, and likely therapy and treatment at different times – the system still largely leaves them managing a high-risk situation on their own until it is too late.

That reality will hang over this case whether or not it is formally litigated under the banner of “mental competency.” If Nick’s defense team raises competency or insanity issues, the trial could become a public referendum on how courts should treat severe mental illness in capital cases. If they don’t, the silence around his mental state will be just as telling, reinforcing how much stigma still shapes what families and lawyers feel able to say.

Expert perspectives: Law, psychology, and the ethics of symbolic death sentences

Legal and psychological experts see several fault lines emerging.

On the symbolic nature of a death sentence under a moratorium

Many scholars argue that seeking death in a state that refuses to execute is less about public safety and more about political signaling.

Professor Carol Steiker, a leading death penalty scholar at Harvard Law School, has argued in similar contexts: “When the state continues to seek death in a jurisdiction where executions are effectively off the table, the punishment becomes largely expressive – a statement of moral condemnation rather than a practical sanction. That raises serious concerns about arbitrariness and honesty in sentencing.”

If Hochman pursues death, he will be asking jurors to choose a punishment they likely know will not be carried out as long as current policy stands. That dissonance can erode public trust in the sincerity and transparency of sentencing.

On mental health and competency

Should the defense raise competency, the case may turn on whether Nick can understand the proceedings and assist his lawyers, not just whether he had a diagnosable psychiatric condition at the time of the killings. In capital cases, courts are especially cautious about executing (or even sentencing to death) individuals with severe mental illness.

Dr. Reena Kapoor, a forensic psychiatrist who has testified in homicide cases, notes in related litigation: “Paranoid psychosis, bipolar disorder with psychotic features, and certain substance-induced states can dramatically impair reality testing and judgment. But the legal thresholds for insanity or incompetence are narrow. Many defendants who were clearly very ill still do not meet those standards under current law.”

The Reiner case may thus highlight a longstanding gap: mental illness that is serious enough to be causally relevant to the crime but not severe enough to satisfy legal definitions of insanity.

On the ethics of family-driven punishment

Victims’ rights statutes like Marsy’s Law are intended to ensure families are not sidelined. But in intrafamilial homicides, that empowerment can become ethically fraught.

Criminologist Mark Umbreit, a pioneer in restorative justice, has argued in similar cases: “When the same family is both grieving the loss of loved ones and grappling with the possible destruction of another beloved member, giving them a quasi-veto over punishment decisions can be cruel as well as impractical. The state must ultimately own its decisions about life and death.”

Data and evidence: How unusual is this case really?

On the surface, the alleged murder of high-profile parents by their son appears extraordinary. In statistical terms, the dynamics are tragically recognizable.

- The Bureau of Justice Statistics has consistently found that a significant portion of homicides occur within families, including adult children killing parents.

- Multiple studies suggest that mental illness or substance abuse – often co-occurring – are present in a large share of parricide cases.

- Nationwide, death sentences in family homicide cases have declined sharply, especially when evidence of psychiatric illness or addiction is strong.

Even in California, where the death penalty is technically available, prosecutors often opt for life without parole in domestic or intrafamilial homicides, reserving capital pursuit for highly aggravated, stranger-on-stranger crimes or murders involving torture, kidnapping, or terrorism.

Given that pattern, the most likely non-political outcome here – regardless of initial charging rhetoric – is a life-without-parole scenario, potentially shaped by plea negotiations if the evidence is overwhelming and the defense seeks to avoid the uncertainties of a capital trial.

Looking ahead: What to watch as the case unfolds

Several key developments will determine not only Nick Reiner’s fate, but the broader lessons this case leaves behind:

- Will prosecutors formally notice the death penalty?

Announcing that death is legally possible is different from actually filing a death notice. That procedural step will be the real test of how far Hochman is willing to go in a state under a moratorium. - Will mental competency or insanity become central issues?

If the defense raises competency, the narrative will shift from a straightforward double homicide to a public examination of Nick’s psychiatric history, treatment gaps, and potential psychosis or impairment at the time of the killings. - How unified is the Reiner family on punishment?

Any public statements from siblings or extended family about sentencing will matter. A family divided – some calling for mercy, others for maximum punishment – would dramatize the limits of Marsy’s Law in resolving deep moral disagreement. - Will this case spark renewed debate over California’s dormant death row?

High-profile victims often galvanize policy debate. If this case ends in a symbolic death sentence, it may intensify calls either to formally abolish capital punishment or to end the moratorium and resume executions. - Does anyone seriously confront the prevention question?

Beyond courtroom strategy, a crucial question remains: what opportunities were missed over the past decade to intervene more effectively in Nick’s life – and what systemic reforms might prevent similar tragedies?

The bottom line

The Reiner case sits at the intersection of grief, mental illness, and a death penalty structure that no longer matches political or practical reality. The law will decide whether Nick Reiner spends his life in prison or receives a symbolic death sentence under a moratorium. But the deeper indictment may fall on a system that repeatedly waits for the worst to happen – then offers only punishment and post-mortem compassion, instead of earlier, sustained intervention when there is still time to change the outcome.

Topics

Editor's Comments

What’s most striking in the Reiner case is how quickly the public conversation has jumped to the death penalty, even though California hasn’t executed anyone in nearly two decades and is under a formal moratorium. That focus reflects a deeper habit in American justice: we are far more comfortable debating how harshly to punish after a catastrophe than asking why the warning signs didn’t trigger serious, sustained intervention earlier. The reporting already documents years of volatility, early behavioral issues, and a long struggle with addiction. Yet there is almost no discussion of what concrete options the family had when Nick was younger—could they have accessed long-term residential treatment, coordinated psychiatric care, or court-ordered support without waiting for a criminal crisis? If those options were inadequate or inaccessible even for a wealthy, well-connected Hollywood family, that should alarm us. It suggests that countless less visible families are in even more precarious situations, with even fewer resources, and that the question we ought to be pressing is not just ‘What sentence will Nick receive?’ but ‘What would it have taken to prevent this from ever becoming a criminal case at all?’

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.