Rob Reiner’s Killing Puts America’s Mental Health–Justice System on Trial

Sarah Johnson

December 18, 2025

Brief

An in-depth analysis of the Rob and Michele Reiner homicide case, exploring Nick Reiner’s mental competency, the limits of rehab, and how addiction and mental illness collide with the criminal justice system.

Inside the Reiner Tragedy: Mental Competency, Addiction, and a Justice System on Trial

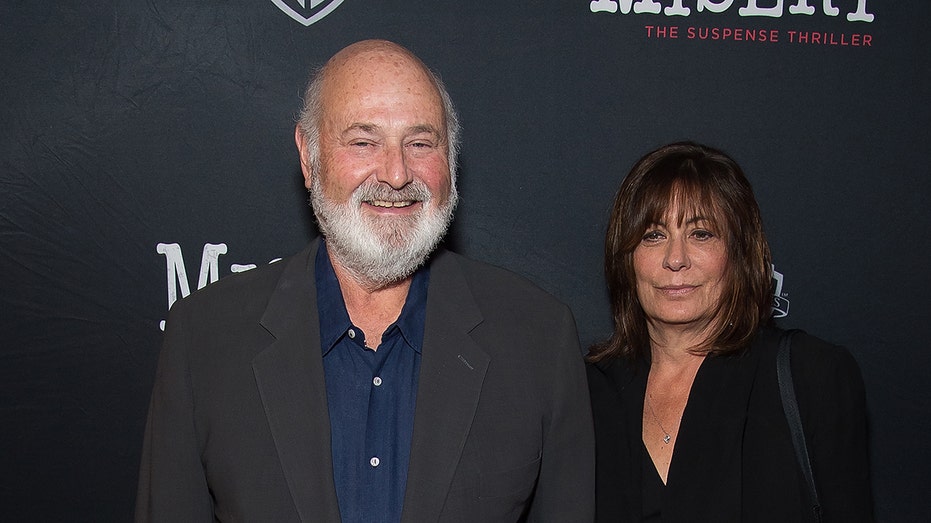

The alleged killing of filmmaker Rob Reiner and his wife, Michele, with their son Nick now charged with first-degree murder, is being framed as a celebrity crime story. In reality, this case sits at the intersection of three of America’s deepest systemic failures: how we treat addiction, how we handle serious mental illness, and how our criminal courts draw the line between punishment and treatment.

What happens next in this case will not just determine whether Nick Reiner spends his life in prison, in a psychiatric hospital, or some combination of both. It will also illuminate a controversial and often misunderstood legal threshold: mental competency to stand trial versus legal insanity at the time of the crime, and how those standards interact with long‑term addiction and possible psychiatric disorders.

The bigger picture: A family’s long public battle with addiction

Long before this double homicide, the Reiner family had already done something unusual in Hollywood: they made their son’s addiction struggles public. The 2015 film Being Charlie, co-written by Nick and directed by his father, was a semi‑autobiographical look at a young man cycling through rehab and relapse. Interviews at the time painted a portrait that now feels tragically prophetic.

By age 22, Nick had reportedly been to rehab 18 times. He himself said, “I just couldn’t get by in these programs. I had resistance every time they tried to reach me.” Rob and Michele publicly admitted they often deferred to treatment professionals instead of listening to their son’s own experience, expressing frustration that the standard rehab model did not seem to work for him.

This history matters because it shows three key things:

- A long‑standing pattern of serious substance use disorder, likely beginning in adolescence.

- Repeated interaction with the treatment system, but without sustained recovery.

- A family that was not in denial, but still struggling to find effective help for a complex condition.

In the United States, this pattern is distressingly common. SAMHSA data suggest that only around 10% of people with substance use disorder receive specialty treatment in a given year, and even among those who do, relapse rates for opioid addiction can exceed 60% within a year of treatment. The Reiners had both resources and access, yet still found themselves trapped in that cycle.

The legal core: Competency vs. insanity, and why the distinction matters

Much of the immediate legal discussion revolves around Nick’s mental competency and a possible plea of not guilty by reason of insanity (NGI). These are related but distinct concepts that are often conflated in public debate.

Competency to stand trial is about the present: does the defendant understand the nature of the proceedings and can he assist his attorney in his defense? If he is found incompetent, the criminal case is paused while he undergoes treatment—often with medication—until he can be restored to competency. That’s why the detail that he was “not medically cleared” to appear in court is so significant: it signals that medical or psychiatric issues may already be affecting the basic functioning required to move the case forward.

Insanity at the time of the crime is about the past: did the defendant, at the moment of the alleged killings, understand what he was doing and know that it was wrong? In California, the legal standard focuses on whether a mental disorder made the person incapable of understanding the nature and quality of the act, or of distinguishing right from wrong.

That’s a deliberately narrow definition. As former federal prosecutor Neama Rahmani notes, simply appearing agitated or argumentative is not insanity in the legal sense. Psychosis, schizophrenia, or delusional states—believing a parent is an alien or demon, for example—are closer to what the law contemplates as potentially exculpatory on grounds of insanity.

Historically, insanity defenses are rare and rarely successful. Studies typically show insanity pleas in less than 1% of felony cases, with success rates in only a fraction of those. The public perception that “criminals get off on insanity” is largely a myth; more often, defendants spend longer under confinement in secure psychiatric facilities than they might have under a determinate prison sentence.

Beyond the sound bites: Addiction, psychosis, and the gray zone

What makes the Reiner case particularly complex is the intersection between addiction and potential mental illness. The law makes a stark distinction: intoxication or drug abuse alone generally does not support an insanity defense. As Christopher Melcher points out, voluntary drug use as such does not qualify as legal insanity.

But the reality on the ground is far messier. Chronic substance use can both mask and trigger psychiatric conditions. Stimulants and some synthetic drugs can induce psychosis that is clinically indistinguishable from schizophrenia while it is ongoing. Long‑term opioid, alcohol, or polysubstance use can alter brain function in ways that complicate questions of intent, impulse control, and perception.

This creates a gray zone the legal system is ill‑equipped to handle: when does drug‑related psychosis become a mental disease for legal purposes? When does a long‑term pattern of addiction and instability—paired with apparent bizarre behavior, as witnesses described at Conan O’Brien’s party—cross the line into genuine incapacity to understand reality?

Witnesses reportedly said Nick was “freaking everyone out, acting crazy, kept asking people if they were famous,” and engaged in loud confrontations with both his parents and others at the party. Those details will be crucial for both sides: prosecutors may argue this reflects volatility but intact awareness of his surroundings; defense lawyers may see evidence of escalating mental instability or a psychotic break.

Why this case is a referendum on the mental health–criminal justice pipeline

Strip away the celebrity names, and the basic story is painfully familiar to psychiatrists, public defenders, and social workers: a person with long‑term addiction, possible untreated or undertreated mental illness, escalating behavioral disturbances, and a family trying—often imperfectly—to find help.

In Los Angeles County, this pattern feeds directly into what experts call the “mental health–criminal justice pipeline.” The county jail system has been described by officials as the largest mental health facility in the United States. The Twin Towers Correctional Facility, where Nick is being held, has thousands of inmates receiving some form of mental health treatment, many of whom cycled through ERs, short‑term rehabs, or under‑funded outpatient programs before landing in custody.

The Reiner case exposes several structural failures:

- Fragmented treatment: 18 rehab stays by age 22 suggests acute interventions without long‑term continuity of care or a truly individualized plan for a resistant, complex case.

- Family system strain: Rob and Michele openly admitted feeling pressured by experts who framed Nick as manipulative and untrustworthy—language common in addiction treatment that can erode family trust and nuance.

- Lack of early diversion: In many jurisdictions, mental health and drug courts are supposed to route high‑risk individuals into more intensive, monitored treatment tracks. Yet diversion hinges on early recognition and cooperation that may not have been achievable for someone in Nick’s position.

What the mainstream coverage is missing

Most coverage focuses on the most dramatic elements: the celebrity party, the argument, the gruesome crime scene, the possibility of a death penalty case. Here are three critical dimensions that deserve far more attention:

- The limits of the “rehab industrial complex.” The Reiners were affluent, connected, and publicly engaged in seeking help—yet Nick himself said, “The program works for some people, but it can’t work for everybody.” This highlights a rarely discussed reality: our dominant 28‑day, group‑based rehab model often fails those with dual diagnoses, trauma histories, or significant resistance. There is little accountability for outcomes, and almost no systemic mechanism to say, “This standard model isn’t working—we need something different.”

- The gap between clinical reality and legal categories. The law still largely treats mental illness as binary: sane or insane, competent or incompetent. Contemporary psychiatry sees a spectrum of functioning, impairment, and fluctuating capacity. The Reiner case may force courts—and the public—to confront how crude those legal boxes are compared to what clinicians know about chronic addiction and psychosis.

- The quiet role of stigma, even in “open” families. The Reiners did more than most to talk about addiction. But even in their own words, you see internalized stigma: Nick framing himself as “not supposed to be out there on the streets,” Michele describing being told he was just a liar and manipulator. Beneath the public candor is a familiar story of shame, fear, and the powerful pull to view a struggling loved one through a purely moral lens.

Looking ahead: Scenarios and stakes

Legally, several key phases are coming:

- Competency evaluation: Given that Nick was not medically cleared to appear, his defense team is likely to push for a formal competency evaluation. If found incompetent, he would be treated—often with antipsychotic or mood‑stabilizing medication—until courts deem him able to participate in his defense.

- Evidence building around mental state: Prosecutors will seek medical records, prior psychiatric evaluations, rehab documentation, and witness accounts from the party and the days leading up to the killings. The defense will look for any history of psychosis, hallucinations, or severe mood disturbance that predates the incident.

- Potential NGI plea: If there is documentation of serious mental illness, the defense may pursue an insanity phase. A key question will be: was any psychosis “substance‑induced” and transient, or part of a broader, underlying psychiatric disorder?

- Death penalty calculus: The presence of a plausible severe mental illness narrative—combined with a public record of long‑term treatment efforts by the parents themselves—could weigh heavily against seeking the death penalty, even if special circumstances technically allow it.

Beyond this single case, policymakers and advocates will be watching for signs that Los Angeles uses this moment to scrutinize how its systems handle people like Nick before tragedy strikes: the availability of intensive, personalized treatment; the responsiveness of mental health services to families in crisis; and the permeability of the boundary between medical and criminal responses.

The bottom line

This is not just a story about a famous family destroyed by violence. It is a stark case study in how addiction, possible mental illness, and a rigid legal framework can converge with catastrophic results.

Whether Nick Reiner is ultimately found legally sane or insane, competent or incompetent, one reality is already clear: the systems that were supposed to help him long before police tape went up in Brentwood were fragmented, inconsistent, and ultimately inadequate. The law will decide his fate. The rest of us should be asking what it would take to keep the next family from following the same path.

Topics

Editor's Comments

There is an uncomfortable question lurking beneath this case: would anything have been different if Nick Reiner were not the son of a famous director, but an unknown man in South Los Angeles? On one hand, his parents’ resources and willingness to seek help gave him access to a level of treatment many Americans never receive—multiple rehabs, public advocacy, and a supportive family. On the other hand, that same celebrity status shapes how the public and legal system will perceive him now: every erratic gesture becomes a headline, and every legal motion is interpreted through the lens of privilege. The larger system, however, behaves remarkably similarly for both the famous and the poor. In both situations, we wait until a person is dangerous enough to be arrested, then try to retrofit mental health treatment into a punishment framework. Whether Nick ends up in prison or a hospital, it will be framed as an individualized failure—his, or his parents’—rather than a predictable outcome of policy choices that starve community mental health care and reward short-term, high-margin rehab models over sustained, evidence-based support. That, more than any courtroom drama, is the indictment this case quietly delivers.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.