Beyond Maduro: How Trump’s New Security Doctrine Turns the Hemisphere into America’s ‘First Line of Defense’

Sarah Johnson

December 18, 2025

Brief

Trump’s blockade of Venezuelan oil and the FTO label on Maduro signal a doctrinal shift: the Western Hemisphere is now America’s ‘first line of defense.’ Here’s the deeper strategy and its risks.

Trump’s ‘First Line of Defense’: Why Venezuela Is Now the Test Case for a Rewired U.S. Hemispheric Strategy

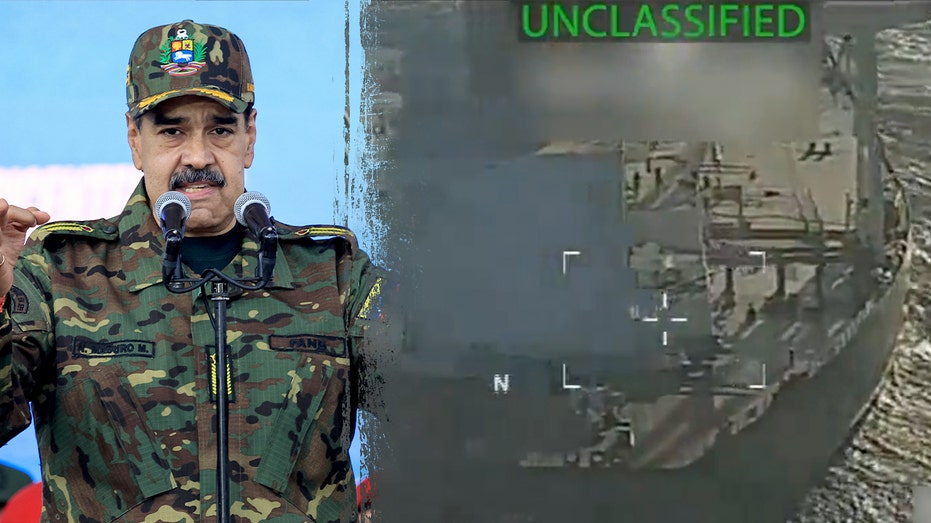

The decision to declare Nicolás Maduro’s government a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) and deploy a sweeping naval blockade against Venezuelan oil tankers is not just another twist in the long U.S.–Venezuela standoff. It’s the clearest operational test of a much bigger shift: a National Security Strategy that reframes the entire Western Hemisphere as America’s “immediate security perimeter” and recasts migration, cartels, and foreign influence as threats on par with more traditional military dangers.

That shift has three core implications. First, it resurrects and hardens a 19th-century doctrine — the Monroe Doctrine — for a 21st‑century world of Chinese loans, Iranian intelligence networks, and Russian military advisers. Second, it blends national security with domestic political anxieties about immigration and crime in a way that will shape policy far beyond Venezuela. Third, it risks creating a classic sanctions‑and‑pressure paradox: the more aggressively Washington squeezes Maduro, the higher the odds of a chaotic collapse that could actually deepen the very instability the strategy claims to prevent.

How We Got Here: From ‘Pink Tide’ to Narco-State

To understand why Venezuela is at the center of this new doctrine, you have to trace two parallel arcs: Venezuela’s own descent from petro‑giant to failed state, and Washington’s evolving view of what constitutes a “security threat” close to home.

At the turn of the century, Venezuela was one of Latin America’s wealthiest countries, with the world’s largest proven oil reserves. Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian revolution channeled soaring oil prices into social programs but gutted institutions, politicized the military, and hollowed out the state oil company PDVSA. After oil prices crashed in 2014, Chávez’s successor, Nicolás Maduro, presided over hyperinflation, mass emigration (over 7.7 million Venezuelans have fled since 2015, according to the UN), and the rise of a hybrid regime where the boundaries between state, party, and organized crime largely disappeared.

Washington’s posture evolved accordingly. Early 2000s U.S. policy toward Venezuela oscillated between uneasy coexistence and selective sanctions. By the late 2010s, the U.S. was openly backing opposition leader Juan Guaidó and imposing sweeping oil and financial sanctions. But there was still a conceptual gap: Venezuela was treated as an illiberal outlier, not the centerpiece of a hemispheric security doctrine.

The new National Security Strategy closes that gap by fusing multiple concerns into a single narrative: Venezuela as a narco‑dictatorship, as a platform for extra‑hemispheric rivals (China, Russia, Iran), and as a generator of migration flows and criminal networks that reach deep into U.S. territory. In this framing, Maduro’s survival is not just a humanitarian or democracy problem; it’s the linchpin of a hostile ecosystem that reaches U.S. borders and streets.

The ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine

The strategy’s reference to a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine is more than rhetorical flourish. Historically, the Monroe Doctrine (1823) was about warning European powers not to recolonize Latin America. Over time, it morphed into a justification for U.S. interventions, from gunboat diplomacy to Cold War coups.

This new corollary updates the doctrine for an era where “incursion” often takes the form of investment, cyber operations, intelligence cooperation, and energy deals rather than troop landings:

- China is now the top trading partner of much of South America and a major lender. In Venezuela, Chinese credit and oil‑for‑loans deals helped keep the regime afloat after Western sanctions.

- Russia has supplied arms, advisors, and advanced systems to Caracas, and uses Venezuela as a diplomatic and intelligence foothold in the hemisphere.

- Iran has deepened ties through fuel shipments, industrial deals, and cooperation between security services. U.S. officials increasingly see that relationship through a terrorism lens.

Labeling Maduro’s regime a Foreign Terrorist Organization effectively fuses these threads. Traditionally, FTO designations target sub‑state actors like Hezbollah or the FARC. Applying that category to a sitting government crosses a conceptual line: it treats an entire state apparatus as a node in a global terror‑criminal network. That opens legal pathways for asset seizures, prosecutions, and military interdictions far beyond existing sanctions tools.

Why Venezuela Is Now Framed as ‘First Line of Defense’

The administration’s logic is straightforward: the Western Hemisphere is the zone where domestic and foreign policy most directly intersect. Three pillars stand out in the NSS:

- Migration control: The strategy openly elevates “mass migration” to a top-tier security threat. With Venezuelans now among the largest migrant groups arriving at the U.S. southern border, the regime’s collapse is seen less as a distant tragedy and more as a direct driver of domestic political and social pressure.

- Narco-terrorism and cartels: U.S. agencies have long accused Venezuelan officials of cooperating with or participating in drug trafficking—embodied in the so‑called “Cartel of the Suns,” networks of military and political elites allegedly moving cocaine through Venezuelan territory. Classifying these actors as terrorism‑linked raises the stakes and justifies more extraterritorial action.

- Foreign adversaries: Venezuela offers Russia and Iran a symbolic and operational beachhead in America’s backyard and provides China a key piece in its global commodity and influence chain. The NSS reframes these relationships not as isolated deals but as part of a coordinated challenge to U.S. regional primacy.

In this sense, the naval blockade is not only about cutting off Maduro’s revenue. It’s also about signaling to Beijing, Moscow, and Tehran that the U.S. is willing to use hard power to police access and assets in the hemisphere, including energy infrastructure and maritime routes.

What’s Overlooked: Economic Realities and Humanitarian Blowback

Much of the political rhetoric frames the blockade and FTO designation as clean, security‑driven moves: squeeze a criminal regime, deny foreign adversaries a platform, and reduce drugs on U.S. streets. What is largely missing is a serious reckoning with three interlocking realities:

- Economic collapse as a force multiplier: Oil accounts for roughly 88% of Venezuela’s export earnings. The economy has already shrunk by more than two‑thirds since 2013. Additional choke points on oil revenue may weaken the regime’s patronage networks, but they also risk further immiserating a population already facing widespread food insecurity and crumbling public services. Previous rounds of sanctions coincided with spikes in migration; a harsher blockade could accelerate those trends.

- Humanitarian vs. coercive policy: The new NSS is explicit about prioritizing migration control and security. But absent a structured humanitarian carve‑out and credible commitments to refugee and asylum burden‑sharing, the most likely short‑term effect of heightened pressure is more people on the move, not fewer.

- Region-wide ripple effects: Countries like Colombia, Brazil, Peru, and Chile already host millions of Venezuelans. Another wave of displacement—especially if accompanied by more violence and criminal fragmentation inside Venezuela—could strain already‑fragile social contracts across the region and fuel backlash politics that themselves tilt toward illiberal or militarized responses.

Escalation Risks: When ‘Maximum Pressure’ Meets a Fragmented State

Roxanna Vigil’s warning about a “power vacuum” gets at a central dilemma: Venezuela is no longer a conventional authoritarian state with a coherent chain of command. It is a patchwork of armed factions, criminal groups, and pro‑government militias that control different territories and revenue streams.

If the combination of financial strangulation and military pressure seriously weakens the central regime without a negotiated transition in place, three dynamics are plausible:

- Territorial fragmentation: Border regions and resource‑rich areas could fall further under the control of non‑state armed groups, including Colombian guerrillas, local “colectivos,” and cartel‑linked organizations.

- Radicalization of security forces: Elements of the military and intelligence services, facing prosecution or extradition if they lose power, may double down on repression or align even more deeply with criminal networks as survival strategies.

- Proxy conflict potential: External actors (Russia, Iran, perhaps Cuba) could seek to preserve influence by backing particular factions—exactly the outcome the NSS claims to prevent.

In other words, uncalibrated escalation against Maduro can paradoxically produce the kind of uncontrolled, multi‑actor conflict that is far harder to manage and that spills over more directly into neighboring states and migration corridors.

Competing Theories of Change: Pressure vs. Negotiated Transition

Jason Marczak underscores a view that has broad backing among mainstream policy analysts: there is no sustainable solution without a real democratic transition that allows Venezuela to re‑enter global markets and rebuild institutions. Where there is far less consensus is on how to get there.

The emerging Trump strategy tilts decisively toward “coercive regime change,” even if that phrase is not used:

- Coercive pathway: Maximize economic and security pressure, delegitimize the regime by labeling it a terrorist organization, and hope that internal fractures or elite defections open a path to a new leadership coalition or transitional authority.

- Negotiated pathway: Use sanctions and international leverage as bargaining chips in structured negotiations that include amnesties, phased sanctions relief, and security guarantees for at least some regime actors, coupled with clear benchmarks for elections and institutional reform.

The administration’s rhetoric—“fortress built on sand,” “narco‑dictatorship,” “terrorist organization”—makes the second approach harder politically. It raises the question Vigil is hinting at: if all key figures are branded terrorists and criminals, who is left to sign and implement a transition deal? The more absolutist the narrative, the narrower the space for pragmatic de‑escalation.

Domestic Politics: National Security Strategy as Electoral Document

The NSS is framed as a strategic blueprint, but it is also an implicitly political document. It reorders threats in a way that aligns closely with the priorities of Trump’s domestic base:

- Migration overtakes terrorism as the top‑line danger.

- Cartels and narco‑terrorism become key villains in a story that connects border security, crime, and foreign policy.

- Military assertiveness is paired with claims of ending “endless wars,” shifting from large‑scale occupations to targeted operations and maritime blockades closer to home.

The Venezuela case thus serves dual functions: it is both a test bed for an updated hemispheric doctrine and a narrative vehicle to demonstrate “toughness” on migration, drugs, and foreign adversaries in a way that resonates domestically.

Looking Ahead: What to Watch

Several indicators will show whether this strategy is reshaping the region or merely adding another layer of pressure to an already strained crisis:

- Scope and enforcement of the blockade: Does it remain tightly focused on Venezuelan state‑linked oil shipments, or expand to third‑country vessels and intermediaries, risking broader trade frictions and legal disputes?

- Behavior of key external players: Do China, Russia, and Iran recalibrate their presence in Venezuela, double down, or shift to more covert forms of support?

- Migration and asylum trends: Any significant uptick in Venezuelan outflows over the next 12–18 months will test the claim that this strategy ultimately stabilizes the “immediate security perimeter.”

- Signals on negotiation: Behind public hardline rhetoric, are there back‑channel talks on transitional guarantees, electoral pathways, or partial sanctions relief?

If the NSS becomes a template for dealing with other fragile states in the region—think Haiti, parts of Central America, or future crises in the Andes—it will mark a generational shift in how the U.S. uses security tools to manage what are fundamentally political and economic breakdowns.

The Bottom Line

The blockade of Venezuelan oil tankers and the FTO designation of Maduro’s regime are less about a single country and more about the architecture of U.S. power in the Western Hemisphere. By elevating the region to “first line of defense,” the Trump administration is reviving an old doctrine, overlaying it with new threats, and betting that harder lines and sharper tools can restore preeminence and contain instability.

The unanswered question is whether a strategy built around maximum pressure, maritime muscle, and terrorism designations can produce a controlled, negotiated transition—or whether it will accelerate the fragmentation of an already broken state, deepening the very migration and security challenges it aims to solve.

Topics

Editor's Comments

The most consequential element in this story may not be the blockade itself but the quiet reordering of what counts as a national security threat. By elevating migration and cartels alongside traditional geopolitical rivals, the National Security Strategy blurs the line between external defense and domestic politics. That makes it more resonant with voters but also more prone to overreach: if every complex social or economic problem is securitized, the default tools become sanctions, interdictions, and military deployments rather than diplomacy, development, and institutional reform. Venezuela is the proving ground for this approach. If maximum pressure yields a negotiated transition and a gradual stabilization, the doctrine will gain enormous legitimacy and could be replicated elsewhere in the hemisphere. But if it leads instead to deeper state collapse, mass displacement, and a mosaic of armed groups with external patrons, the U.S. will have helped create a more fragmented, less governable neighborhood that is harder—not easier—to manage. The underlying question is whether Washington is prepared to pair hard power with long‑term investment in governance and reconstruction, or whether policy will remain locked in a punitive cycle that treats symptoms while worsening the disease.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.